Income tax planning prior to the emigration and immigration of natural persons between Germany and Switzerland

By Dr. Peter Happe, Tax Advisor/FB Internat. Tax Law/C.P.A., Cologne and Zurich,

Samuel Kistler/Dipl. Tax Expert/Dipl. Auditor, Zurich

Moving from Germany to Switzerland and vice versa is relatively unproblematic due to the still existing Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons between the EU and the Swiss Confederation. However, such a move has tax implications that can quickly turn into a nightmare without careful planning and consideration. While Switzerland deals pragmatically with the departure of its taxpayers, if they are natural persons, and does not put any obstacles in the way of moving abroad, this is not the case in Germany. Germany has placed small and large tax hurdles in the way of natural persons leaving the country, which one should at least roughly know and which should not be overcome without tax advice and not too short. In particular, those leaving the country often overlook the subsequent deadlines and the resulting taxation obligations.

1. Emigration from Germany from an income tax perspective

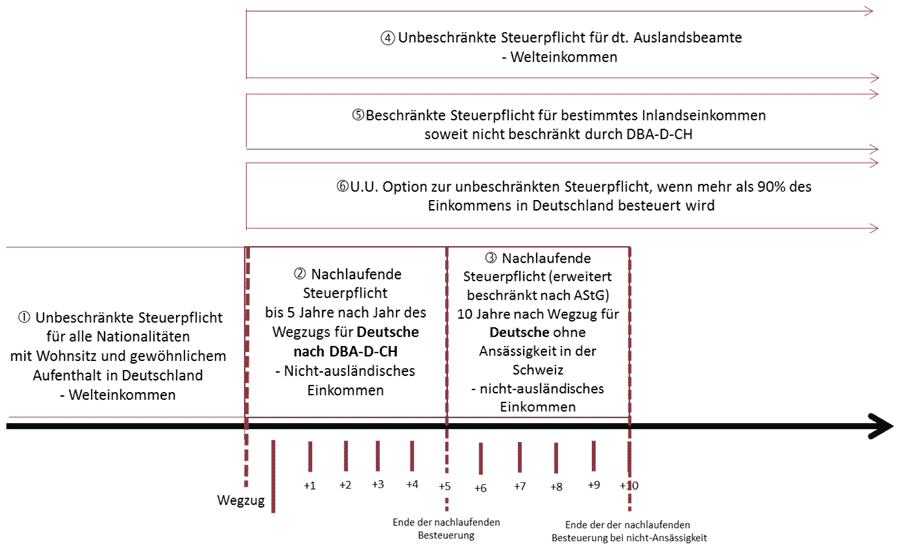

The emigration of natural persons from Germany to Switzerland, which from a German perspective has low taxes, is not welcomed by the German legislator and the German tax authorities and is punished by taxes. This is mainly due to §§ 2 -5 German Foreign Tax Act – AStG. The AStG alone would not be sufficient to trigger taxation in Germany. As a rule, a corresponding opening clause for taxation in the double taxation agreement for income tax and wealth tax between Germany and Switzerland (hereinafter DBA-D-CH)1 must also be added. These can be found primarily in Art. 4 para. 3 and para. 4 DBA-D-CH, but also in Art. 13 para. 4 DBA-D-CH. The deadlines to be observed are dealt with in the following Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Subsequent deadlines for a move from Germany to low-tax Switzerland.

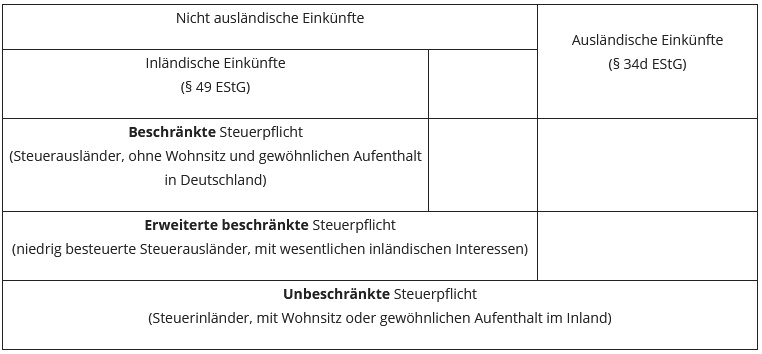

Ad 1: German income tax law taxes the worldwide income of domestic taxpayers as so-called unlimitedly taxable persons, § 1 para. 1 German Income Tax Act – EStG. Taxation is limited by existing double taxation agreements or EU directives or other international law agreements.2 Domestic taxpayers are persons of any nationality with a domicile according to § 8 German Fiscal Code – AO or habitual residence according to § 9 AO of more than 6 months in the year in Germany. A domicile already exists if a modest place to stay is maintained in Germany, i.e. a hunting lodge over which one has free disposal and key control. It does not matter whether the apartment is rented, purchased or regularly made available free of charge by third parties at the request of the taxpayer.

A domicile is also established in Switzerland according to Art. 4 para. 2 DBA-D-CH even if the domicile or habitual residence is in Germany, if a further domicile/permanent home is established in Switzerland and the center of vital interests is moved there, i.e. closer personal and economic relations are established in Switzerland. Even if Germany then falls back into the position of the so-called source state according to the DBA-D-CH, unlimited tax liability remains in Germany (Art. 4 para. 3 DBA-D-CH), so that worldwide income must be declared in Germany (possibly with exemption from Swiss income or crediting of Swiss tax on income taxed in Switzerland)3. In the DBA-D-CH – unlike in other DBAs concluded by Germany – the special feature was agreed that a move to Switzerland is only recognized for tax purposes if not only the habitual residence is moved to Switzerland, but also every domicile in Germany is abandoned. According to Art. 4 para. 3 DBA-D-CH, Germany is unilaterally granted the right of “overarching taxation”, according to which a taxpayer with a domicile4 in Germany must tax not only German income, but worldwide income unaffected by the DBA-D-CH. Insofar as Switzerland would tax this income, it would be credited against German tax. Only the income that is exempt from German tax anyway according to Art. 24 para. 1 no. 1 DBA-D-CH, such as income from permanent establishments, income from self-employment in a fixed facility and dividends, as well as income from non-self-employment to be taxed in Switzerland according to Art. 15 DBA-D-CH, remain tax-free subject to progression, i.e. determining the tax rate. In this way, people who have moved to Switzerland with a domicile or habitual residence in Germany are taxed at the regularly higher German tax rate, as if they had not moved at all. Therefore, if a tax emigration is to succeed, not only must a domicile and habitual residence be established in Switzerland, but no domicile and no habitual residence may be maintained in Germany.

It is always problematic if an emigrant – regardless of nationality – who has been subject to unlimited tax liability in Germany for a total of 10 years, moves to Switzerland (or another country) and holds capital investments of 1% or more in domestic and foreign corporations in private assets. The exit tax is levied without the corporation having to relocate its registered office or management. The exit taxation serves to ensure the taxation of hidden reserves in shares in corporations quasi in the last second of the exit within the meaning of § 17 EStG before Germany loses the right of taxation to the future state of residence according to Art. 13 para. 3 DBA-D-CH. In this case, the hidden reserves in the shares of the corporations are taxed as if the shares had been sold at fair market value (fictitious disposal) if the shareholding on the day of departure or in the last five years before departure amounts to 1% or more of the capital of the corporations (§ 6 para. 1 AStG).5 The holding period of the legal predecessor (donor or testator) is attributed to the emigrant (§ 6 para. 2 AStG). In accordance with the purpose of this standard, circumventions of the taxation of such capital shares in Germany are prevented, and other transfers of shares abroad through donations, inheritances, conversions, contributions to a foreign permanent establishment or the like are also taxed.6 Above all, the law not only refers to the abandonment of the domicile or habitual residence and thus the termination of unlimited tax liability under domestic German tax law, but also, without termination of unlimited tax liability, to the establishment of a domicile or habitual residence abroad, on the basis of which the taxpayer becomes resident abroad (Art. 4 DBA-D-CH and Art. 4 OECD-MA). Even if resident abroad, unlimited tax liability in Germany remains in principle if a domicile and a permanent residence remain in Germany.

Even if the exit tax with the income tax “only” leads to a taxation of the determined capital gain to 60% according to the partial income procedure in § 3 No. 40 letter c) EStG at the individual tax rate of at least up to 47.5% plus possibly church tax of 8-9%, the taxation without inflow of liquidity from the sale of the investment is a real obstacle to emigration. In addition, the exit tax can certainly lead to double or multiple taxation with German and foreign income tax as well as inheritance and gift tax, as the following example shows.

Example: The entrepreneur U, who has lived in Cologne all his life (unlimited tax liability and residence in Germany), dies and leaves his son S, who stayed in Switzerland after studying in St. Gallen and is resident in Zug, the shares in GmbH G, the Aktiengesellschaft A in Zurich and the LLC L (a corporation) in Jersey, USA. U held 25% or more of the capital in all companies. The companies G and A have a positive company value at the time of death, the company L has a negative value.

Due to the death, the shares are transferred to a Swiss taxpayer and German income tax is levied on all shares in corporations as if they had been sold. According to a recent ruling by the BFH, the negative company value of L may not be deducted from the positive company values G and A or offset against other income.7 In addition, German inheritance tax is payable. In addition to this double taxation in Germany, it must be checked whether US tax is also incurred, which would be the case, for example, if the father is a US citizen by birth.

If the father U had acquired the shares of G GmbH before 1999, it would have been possible to additionally check which part of the increase in value is tax-free. Increases in value that had already occurred before 1999 were due to the change in the tax-free participation rates from ≤ 25% to last ˂1% (until 2009) tax-free until the change of the participation rates in §§ 17, 6 AStG. The part of the increase in value that arose in the period after 1998 is taxable.8 Due to the extension of the exit tax to foreign corporations in 2006, one could at least ask the question whether it is constitutional that increases in value up to 2006 in foreign corporate shares are also subject to the exit tax.

As an exception, if there is an intention to return to Germany within five years (extendable by another five years), taxation is initially waived upon application (§ 6 para. 3 AStG). The tax due can be paid in five interest-bearing installments upon application and against provision of security if the immediate levy constitutes a considerable hardship (hardship clause in § 6 para. 4 AStG), or for five or ten years against provision of security if applied for under § 6 para. 3 AStG. The deferral is to be revoked if the shares are sold or the company is liquidated. If the value of the shares falls after the departure, this is generally irrelevant for German taxation (irrelevant?).

In the case of a departure within the EU and the EEA area, citizens of an EU or EEA country are granted an interest-free deferral without provision of security (§ 6 para. 5 AStG). It is at least gratifying that the European Court of Justice, after submission by the Baden-Württemberg Tax Court, considers the regulation of § 6 para. 5 AStG to be contrary to European law insofar as the standard contradicts the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons between Switzerland and the EU (submission decision of the FG Baden-Württemberg of June 14, 2017, 2 K 2413/15; Ref. ECJ C-581/17, Rs. Martin Wächtler against Finanzamt Konstanz).9 This does not achieve income tax exemption for emigration to Switzerland either, but the tax would be permanently deferred as in the case of emigration to an EU/EEA country without collateral and interest. As a result, emigrants to Switzerland should also benefit from the regulation of § 6 para. 6 AStG, according to which the assessed but not collected tax is to be reduced in the event of emigration to Switzerland if it turns out that the value originally set in Germany for the exit tax is too high in the event of a later sale or liquidation of the company.

It is of little help, at least with regard to Switzerland, that the part of the hidden reserves that was already taxed in Germany upon departure is to be set as acquisition costs in Switzerland according to Art. 13 para. 5 DBA. In most cases, this attribution of the historical acquisition costs to the departure value is likely to be ineffective, because in Switzerland the capital gains from shares in corporations may be tax-free anyway after a holding period.

The participation in commercial sole proprietorships or (originally commercial) partnerships in Germany and abroad is not subject to exit taxation in Germany, provided that the permanent establishments within the meaning of § 12 AO or Art. 5, 7 DBA-D-CH in Germany are retained and neither individual assets (§ 4 para. 1 sentence 4 EStG, possibly favored according to § 4g EStG; § 6 para. 5 sentence 1 EStG; § 12 para. 1 KStG) nor the entire business are transferred abroad (§ 16 para. 3a EStG, possibly favored according to § 36 para. 5 EStG). Thus, a move by co-entrepreneurs, i.e. partners of commercial or freelance partnerships or commercial or freelance sole proprietors, is harmless if they do not take any assets across the border.10 This removal of assets is referred to as detachment.

The usual arrangements in the past for contributing shares in corporations to commercially dominated or so-called upwardly infected11 German partnerships within the meaning of § 15 para. 3 EStG are no longer recommended arrangements after a change in case law and legislation by inserting § 50i EStG.12 This is because the Federal Fiscal Court had decided that only original commercial partnerships and not commercially dominated or infected partnerships establish a permanent establishment in Germany under the DBA.13 Commercial infection and domination are legal institutions unknown in DBA law, which is why only original commercial partnerships can establish a permanent establishment.14

The preceding explanations result in some design options for avoiding exit taxation according to § 6 AStG15:

- Domicile management: In the case of a planned departure, the domicile in Germany should not be abandoned or moved abroad without careful consideration without taking one of the measures described below. Likewise, no residence should be established in Switzerland while maintaining German unlimited tax liability, because this already triggers the exit tax. This means that in the case of a second domicile in Switzerland, the habitual residence in Germany and the closer personal relationships within the meaning of Art. 4 para. 2 DBA-D-CH should remain there.

- Conversion of a domestic corporation into an originally commercially active GmbH & Co. KG: By conversion, only the open taxed reserves at the level of the shareholder are subjected to taxation like profit distributions. Otherwise, the book values can be transferred in a tax-neutral manner, i.e. unlike in the case of departure, the shares are not subject to a fictitious liquidation of all hidden reserves including goodwill. However, it should be noted that after a conversion, the shares are subject to a blocking period of five years with regard to trade tax according to § 18 para. 3 UmwStG. 16

- Contribution of the shares to an originally commercial GmbH & Co. KG within the meaning of § 15 para. 1 sentence 1 EStG: It is crucial that the shares are also functionally assigned to the permanent establishment, which is only the case if the shares serve to fulfill the commercial permanent establishment function and thus become business assets.17 Shares in an asset-managing GmbH & Co. KG are just as little protected from exit taxation as shares in an originally commercial GmbH & Co. KG, which, however, do not serve the originally commercial permanent establishment function; they are considered private assets. Whether the KG is commercial and the shares are to be assigned to the permanent establishment can only be clarified with certainty by means of a binding ruling.

- Lateral infection in the sense of an enrichment of an asset-managing GmbH & Co. KG, which holds equity investments or into which equity investments are contributed, into an originally commercial GmbH & Co. KG through a commercial activity within the meaning of § 15 para. 1 no. 1 EStG: An asset-managing GmbH & Co. KG, which holds domestic and foreign investments in corporations without being commercially active, does not shield – like commercially dominated corporations – from the exit taxation. If necessary, these companies can be assigned active management functions, so that it is a management holding, which only succeeds with at least two investments. Whether an infection by a commercial activity is sufficient and whether the shares are functionally related to the activity of the commercial permanent establishment function is a question of fact and should, in case of doubt, be accompanied by a binding ruling.

- Sale of the shares and right of repurchase18. Depending on the age of the seller, the purchase price is significantly lower than the fair value of the shares due to the reserved usufruct. Upon return, the sale is reversed subject to a condition subsequent or the shares are repurchased.

Transfer of the shares, possibly free of gift tax, to a natural person or a corporation (domestic foundation) withreservation of usufruct19 , combined with a right of withdrawal from the donation upon return to Germany. The strict requirements of §§ 13a, 13b ErbStG must be taken into account and examined very carefully.- Granting of call options: It is occasionally recommended that emigrants have call options granted to them instead of shares in domestic and foreign corporations. Until exercised, the call options would not be considered shares within the meaning of § 17 EStG/§ 6 AStG. Here, however, it is argued as a precaution that a call option on more than 1% of shares in a corporation as a so-called “expectancy” within the meaning of § 17 para. 1 sentence 3 EStG may well be subject to exit taxation, even if no economic ownership is transferred before the call option is exercised.20 Furthermore, it should be noted that Art. 13 para. 4 DBA-D-CH in the case of holdings of more than 25% in German corporations knows a subsequent taxation of the capital gain in Germany, which in most cases has a declaratory effect due to § 6 AStG. When an option is exercised, according to the unclear wording of Art. 13 para. 4 DBA-D-CH, § 49 para. 1 no. 1 lit. e) EStG could intervene here and tax the capital gain in Germany. Therefore, after moving from Germany to Switzerland, the sale of more than 25% of the shares would have to be waited for until five years have passed.

With all structuring options, it must be accepted that the shares in Germany not only remain liable for income tax, but also for inheritance tax.

Ad 2: In principle, German taxation is not linked to nationality. Exceptions, however, can be found in the case of emigration, especially to Switzerland, according to DBA and according to the AStG. Germans who have been subject to unlimited tax liability in the last ten years for at least five years are taxed in Germany with their non-foreign income in the year of their emigration and for another ten years “subsequently” if they retain significant economic interests in Germany and move to a low-tax country (§ 2 AStG). A significant economic interest in Germany is already presumed according to § 2 para. 3 AStG if, among other things, shares in a German corporation of ≥ 1%, a participation > 25% in a German partnership exist or an income-generating asset of more than EUR 154,000 is located in Germany, which is already the case with a rented apartment in Germany. A low taxation within the meaning of § 2 para. 2 AStG exists if, with a fictitious income of EUR 77,000, the ordinary tax burden abroad is one third lower than in Germany or a preferential taxation exists, unless the actual foreign burden is demonstrably at least two thirds of the burden in Germany. This low taxation should be given in most Central Swiss cantons. Further requirements are that the non-foreign income exceeds EUR 16,500 and the domestic tax is not exceeded in the case of an assumed unlimited tax liability. 21

This subsequent taxation is also referred to as extended limited tax liability and essentially includes the following non-foreign income from the perspective of Germany22:

In the negotiations for the income tax double taxation agreement with Switzerland, Germany has reserved a corresponding opening clause in Art. 4 para. 4 DBA-D-CH and allows a subsequent taxation for the year of emigration and the following five years. The subsequent taxation is only not applicable if Germans move to Switzerland to take up an employment relationship in Switzerland or to marry a Swiss or a Swiss woman. Through the interplay of DBA and § 2 AStG, the subsequent taxation only affects Germans, but not German-Swiss dual citizens and also not persons with a non-German citizenship.

If the extended limited tax liability applies, then the non-foreign income is assessed in Germany. A special feature is that, unlike the limited tax liability discussed below, an assessment takes place in Germany and the foreign, non-taxable income is taken into account in the progression proviso to determine the tax rate, § 2 para. 5 AStG.

An avoidance of the extended limited tax liability by establishing a foreign corporation in which foreigners such as Swiss hold more than 50% of the shares and in which passive non-foreign income within the meaning of §§ 7, 8 and 14 AStG is generated (so-called interposed companies), then does not succeed. Rather, the interposed company is treated transparently for the duration of the attribution and the income is attributed to the emigrant on a pro rata basis. This is not for 10 years, but according to Art. 4 para. 4 DBA-D-CH still for five years after the year of emigration. This is an abuse prevention provision that does not change anything in the taxation of the Swiss corporation itself.23 For active non-foreign income, the interposition of a Swiss corporation and also the interposition of partnerships within the meaning of § 20 AStG can therefore make sense.

Ad 3: The period of 5 years of subsequent taxation after the year of emigration is extended to ten years if an emigrant does not become resident in Switzerland or in another country according to DBA. No residence exists, for example, if the German income of the emigrants in some cantons of Switzerland is subject to preferential taxation such as lump-sum taxation (taxation according to expenditure according to Art. 14 DBG and Art. 6 StHG) (Art. 4 para. 6 DBA-D-CH). In these cases, the emigrants also do not benefit from treaty benefits such as the reduction of German withholding tax on dividends according to Art. 10 para. 1 letter c) DBA-D-CH, the elimination of withholding tax on interest according to Art. 7 DBA-D-CH and the non-taxation of capital gains from investments in German companies according to Art. 13 para. 5 DBA-D-CH. A way out is the modified expenditure taxation permitted in Switzerland, in which the German income is subject to taxation in Switzerland. 24

It is also occasionally overlooked that the extended limited tax liability can also be applied if the emigrant initially has no significant economic interests upon emigration, but subsequently acquires assets in Germany and thereby becomes subject to extended limited tax liability within the five- or ten-year period.

Ad 4: Diplomats and consular officials residing in Switzerland who are paid by a public fund and persons closely associated with them, such as family members belonging to their household (so-called extended unlimited tax liability), remain subject to unlimited tax liability in Germany if they have German citizenship, even if they have no domicile or habitual abode in Germany (§ 1 para. 2 EStG, Art. 29 DBA-D-CH).

Ad 5 : The limited tax liability according to § 1 para. 4 EStG remains indefinitely for emigrants who give up their domicile and habitual abode in Germany – at the latest from the tenth year after emigration abroad – as long as they receive types of income in Germany within the meaning of § 49 EStG. The types of income mentioned in § 49 EStG are only not taxed in Germany if and to the extent that the DBA-D-CH of Switzerland assigns the right of taxation. The limited tax liability is particularly characterized by the fact that it disregards the personal circumstances of the taxpayer and, for example, does not allow the deduction of special expenses and allowances as well as the splitting tariff for married couples. However, also for certain income such as capital income, wage income and income from artistic, sporting, entertaining or similar performances in Germany as well as license income, the law provides for a final withholding tax effect, according to which deductions due to domestic taxpayers are not granted to foreign taxpayers.25 In individual cases, this can be so disadvantageous, for example, in the case of high loss carryforwards or financing costs in connection with capital income, that either the option for unlimited tax liability according to § 1 para. 3 EStG treated below should be chosen or a domicile in Germany should be established.

Ad 6: Even without a domicile or habitual abode in Germany, the legislator grants persons domiciled in Switzerland the option to apply for unlimited tax liability if domestic income within the meaning of § 49 EStG exists and the domestic and foreign income is subject to German income tax to 90% or the foreign income does not exceed the basic allowance according to § 32a para. 1 sentence 2 no. 1 EStG in the amount of currently EUR 9,408.26 This can be particularly useful with regard to the deduction of maintenance payments and the spousal splitting, even if the recipient or spouse lives in Switzerland, even if according to the wording of § 1a EStG the privilege is only to be applied to EU/EEA family members. The tax authorities have extended this privilege to Swiss citizens (Notes on § 1a EStG keyword “Change of domicile» EStR 2019). However, persons who opt for unlimited tax liability are not considered to be resident in Germany. 27

Whether the option for unlimited tax liability is opportune should not only be decided with regard to one year. The option for unlimited tax liability can certainly be accompanied by other disadvantages, for example within the meaning of § 2 or § 6 AStG.

2. Emigration from Switzerland from an income tax perspective

Also before the emigration of natural persons from Switzerland to Germany, some considerations are useful. From a Swiss perspective, the following emigration scenarios can basically occur:

- Transfer of residence to Germany (change of residence) and cancellation of secondary tax domiciles

- Only cancellation of secondary tax domiciles (properties, business establishments, permanent establishments) without transfer of residence to Germany

- Transfer of residence to Germany (change of residence) while maintaining a secondary tax domicile

The following explanations focus essentially on the income tax effects of a change of residence according to DBA-D-CH from Switzerland to Germany (scenarios 1 and 3). The starting point is always an existing unilateral tax liability due to personal affiliation in Switzerland.

In a first step, the general taxation principles are explained and then the tax consequences for specific assets are presented.

2.1 General taxation principles

2.1.1 Swiss Foreign Tax Act

The Swiss foreign tax law is not regulated in a separate law, but within the respective laws (DBG28, StHG29). Those articles determine to what extent Switzerland claims the right of taxation for persons with foreign connections (including emigration). The right of taxation additionally requires a corresponding opening clause in the DBA-D-CH.

2.1.2 Residence

In the case of personal affiliation according to Art. 3 DBG as well as an assignment of residence according to Art. 4 DBA-D-CH to Switzerland, the tax liability according to Art. 6 para. 1 DBG is unlimited, that is, the tax liability in principle extends over the entire domestic and foreign income of the natural person. However, this right of taxation is restricted both by unilateral law (exemption of foreign business establishments, permanent establishments and properties) and by the DBA-D-CH.

2.1.3 Taxable income in general

In principle, all recurring and one-off income of natural persons assigned to Swiss tax sovereignty is subject to Swiss income tax (income general clause Art. 16 para. 1 DBG).

2.1.4 Tax-systematic realization

In the case of emigration, assets are transferred to Germany and thereby withdrawn from future taxation by the Swiss tax authorities. The question arises whether the existing hidden reserves (on the assets transferred to Germany) are covered by a Swiss tax standard in the case of emigration.

In the absence of an actual sale, only a tax-systematic realization can occur in the case of emigration. A tax-systematic realization is not restricted by Art. 13 DBA-D-CH, although there only the term “sale” is mentioned. Outside the core of the term, the treaty-law scope of the term sale is determined by domestic law. Unless the context requires otherwise, the undefined term according to Art. 3 para. 2 DBA-D-CH has the meaning that it has in the application period according to the law of that state to which the agreement applies. A state may also tax such transactions that it equates to a sale. 30

Specifically, Switzerland is not prevented by Art. 13 DBA-D-CH from taxing exit cases (tax-systematic realizations) by transferring economic goods from its tax sovereignty to Germany (provided that they are based on the arm’s length principles developed for Art. 7 and 9 DBA-D-CH or withstand them). 31

2.2 Movable private assets

Capital gains from the sale of movable assets in private assets are explicitly tax-free according to Art. 16 para. 3 DBG. Due to their tax exemption under unilateral law, the question of a tax-systematic settlement of the capital appreciation gain in the event of a change of tax residence to Germany is unnecessary. There is no legal norm for the taxation of the corresponding assets, which is why they can be transferred to Germany tax-free.

However, it should be considered that in Germany the sale of private capital investments that were acquired after January 1, 2009 is always taxable. Accordingly, such accrued, book capital gains are latently subject to tax. The German tax authorities do not know any step-up possibilities in this regard. Before moving in, consideration should be given to the tax-free sale of securities and investments in Switzerland and the repurchase in Germany. The corresponding stamp tax consequences must be taken into account.

2.3 Immovable private assets

Capital gains from the sale of immovable private assets are tax-free at the federal level, but are subject to a real estate gains tax at the state level. Since the tax base also remains liable in the case of a change of residence with Switzerland according to Art. 21 DBG, Art 12 and Art 4 StHG as well as Art 6 and Art. 13 DBA-D-CH (scenario 2), the question of a tax-systematic settlement in the event of emigration is also unnecessary here. The taxpayer remains taxable as the owner of a Swiss property due to economic affiliation.

However, the Swiss real estate ownership also becomes taxable in Germany due to the emigration. Unlike Switzerland, Germany only credits the corresponding Swiss tax (Switzerland exempts the income). Accordingly, depending on the case constellation, the tax is raised to the German level (e.g. in the case of rental income). In addition, a sale of a Swiss property in Germany is only tax-free after 10 years in the case of third-party rental and 2 years in the case of owner-occupation.

2.4 Business assets

According to Art. 18 para. 1 DBG, all income from a commercial, industrial, agricultural and forestry business, from a liberal profession and from any other self-employed activity is taxable.

According to Art. 18 para. 2 DBG, income from self-employment also includes all capital gains from the sale of business assets. The transfer of business assets to foreign businesses or permanent establishments is equivalent to a sale.

According to Swiss terminology, business assets are assets that are associated with a business operation according to the preponderance method. Under certain circumstances, this property may also include shares in corporations (e.g. stock corporations) assigned to the business assets.

In this context, only partnerships are eligible as legal forms for business enterprises, i.e. sole proprietorships, general partnerships and general or limited partnerships.

If, together with a relocation of residence in accordance with Scenario 1, business assets also leave Swiss tax sovereignty and are transferred to a German business or permanent establishment, this leads to the settlement of hidden reserves. On the other hand, there is no exit tax for hidden reserves on those assets and liabilities that remain attached to the Swiss tax authorities (in a secondary tax domicile in accordance with Scenario 3).

For the valuation of the corresponding hidden reserves, the disposal value would have to be used based on the wording of Art. 18 para. 2 DBG (disposal fiction). In the case of a disposal fiction, an original goodwill would have to be taken into account. 32

Because Art. 18 para. 2 DBG only represents a profit demarcation standard, the focus should not be on the “literal meaning”, but on the “normative meaning” based on a substance-oriented economic approach. It is therefore necessary to examine how the hidden reserves are to be valued in each case, taking into account the specific circumstances and the specific facts33. Accordingly, it is also conceivable that a liquidation fiction that is more tax-attractive than the disposal fiction can be used.

Based on the wording of Art. 18 para. 2 DBG, it appears at first glance that a tax-systematic settlement must be carried out immediately when the tax-triggering event occurs. There is no published and established administrative practice in Switzerland in this regard; however, it appears that the tax authorities generally want to assess this issue from an exit tax perspective and tend to prefer immediate settlement to deferred settlement34. In particular, deferred taxation must be examined if unlimited tax liability in Switzerland is not terminated by the transfer process. However, it is undisputed that an immediate settlement must take place if tax liability in Switzerland is definitively terminated.

The immediate taxation is partially criticized in the literature and there are demands for a postponement due to the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons between Switzerland and the EU until the actual realization of the assets35. These demands are given additional weight by the decision of the ECJ (judgment of February 26, 2019 RS C 581/17), but should not have any direct consequences for Switzerland due to the lack of binding effect.

2 Reference to the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court of December 15, 2015, 2 BvL 1/12, IStR 2016, 191.

3 See BFH judgment of October 23, 2018, I R 74/16, BFH/NV 2019, 388.

4 Although the DBA speaks of a permanent establishment. The term permanent establishment according to the DBA should be largely identical to the term residence according to EStG/AO in most cases. Exceptionally, a residence does not exist if the apartment “is used exclusively for recreational, spa, study or sports purposes according to its character and location” and “is demonstrably only used occasionally and not for the purpose of pursuing economic and professional interests”. See Minutes of the negotiations on the DBA-Switzerland 1971 of June 18, 1971, on Art. 4 para. 2 and para. 3. See BFH judgment of June 5, 2007, I R 22/06, BStBl. II 2007, 812 on the term residence.

5 It must also be examined in principle whether the disposal fiction of § 6 AStG triggers a disposal within the meaning of the subsequent tax provisions of § 13a para. 5 ErbStG (denying Troll/Gebel/Jülicher, § 13a, Rz. 178).

6 The relocation or conversion of a domestic corporation fails due to the exit tax rules for corporations such as in § 17 para. 5 EStG and § 12 KStG; see Schmidt, PIStB 2013, p. 41 and p. 76.

7 See BFH judgment of April 26, 2017, I R 27/15, DStR 2017, 1913. Among other things, the possibilities of loss utilization in corporation shares in the event of emigration, Kraft/Gräfe, IWB 2016, 384.

8 See decision of the BVerfG of July 7, 2010, 2 BvR 748/05, BStBl. II 2011,16.

9 See Wilke, PIStB 2019, p. 291.

10 According to § 1 para. 3 sentence 9 to 12 AStG, the transfer of functions, business opportunities and intangible assets, such as know-how and a customer base, and their use abroad is also harmful from a tax perspective.

11 For the current legal status of the infection, see Korn/Scheel, DStR 2019, 1665.

12 See BFH judgment of April 28, 2010, I R 81/09, BStBl. II 2014, 754; Pohl/Raupach, DBA, § 50i EStG and commercially oriented partnerships, in Wassermeyer, Double Taxation Agreements, Festgabe, p. 351; Schaumburg, International Tax Law, 4th edition, 295-298.

13 At least in the non-DBA case in the so-called Chile judgment, the BFH has revised this view, judgment of November 29, 2017, I R 58/15, IStR 2018; 348.

14 See BMF letter of September 26, 2014, BStBl. I 2014, 1258, Tz. 2.3.3. for DBA and non-DBA cases. See Hoheisel, IWB 2008, 2010. With regard to a non-DBA case, the BFH has at least fundamentally affirmed the commercial character, BFH judgment of April 26, 2017, I R 27/15, DStR 2017, 1913.

15 See Kleine/Rippert, IStR 2019, 439,

16 The proposal to only hold an atypical silent participation in a German corporation if there is an intention to emigrate goes in a similar direction. See Bron, IStR 2016, 26. In the relationship between Germany and Switzerland, however, an atypical silent partnership triggers high withholding taxes in Germany.

17 See Wassermeyer in Wassermeyer, DBA, as of Dec. 2018, OECD-MA Art. 13, Rz. 77a. Reference also to § 1 para. 5 AStG and § 6 Betriebsstättengewinnaufteilungsverordnung – BsGAV and Haun/Klumpp, Allocation of shares to the business assets of a partnership, IStR 2018, 661.

18 See Strahl in Kösdi 2007, p. 15657, Tz. 20; BFH judgment of August 7, 2004, VIII R 28/02, BStBl. II 2005, 48; H 17 para. 4 EStR 2019 “Re-transfer”.

19 See Stümper, GStB 2015, 171; H 17 para. 4 EStR 2019 “Reserved usufruct”.

20 See BFH judgment of December 19, 2007, VIII R 14/06, BStBl. II 2008, 659; H 17 para. 4 EStR “Option right”. See also BFH judgment of July 11, 2006, VIII R 32/04, BStBl. II 2007, 296 on the double option, through which economic ownership can pass to the option holder. In this respect, the taxation according to § 6 AStG/§ 17 EStG differs from the taxation of non-tradable stock options that are granted to an employee at a reduced price. Non-tradable stock options are only subject to German wage tax when they are exercised. In H 17 para. 4 EStR “Economic ownership”, the tax authorities write somewhat contradictorily to the above judgment with regard to the BFH judgment VIII R 14/06 that economic ownership can only be established for acquisition options if, according to the typical course of events that is decisive for the economic assessment, an exercise of the option right can actually be expected.

21 See also Kubaile/Suter, Der Steuer- und Investitionsstandort Schweiz, 3rd edition, on the requirements. 2015, 534-537.

22 See the enumerative listing in the BMF letter of May 14, 2004, Tz. 2.5.0.1 and Tz. on non-foreign income. 2.5.0.2. According to § 2 para. 4 AStG, the income of a so-called Interposed Company within the meaning of § 5 AStG must also be declared as income with extended limited tax liability.

23 See Rundshagen, in Strunk/Kaminski/Köhler, AStG § 5, Rz. 26. Flick/Wassermeyer/Kempermann, DBA Switzerland, Art. 4, Rz. 239 derive the subsequent taxation with the case law of the BFH, judgment of July 12, 1989, I R 46/85, from Art. 4 para. 11 DBA-D-CH.

24 See Kubaile/Suter, Der Steuer- und Investitionsstandort Schweiz, 3rd edition 2015, 292; Kolb/Kuabile, Kompaktkommentar zum DBA Deutschland Schweiz, 3rd edition 2015, p. 32 f.

25 See Schaumburg, International Tax Law, 4th edition 2017, 188-197 and 247-263.

26 See Schaumburg, International Tax Law, 4th edition 2017, 148 f.

27 See BMF letter of January 25, 2000, DB 2000, 354.

28 Federal Act on Direct Federal Tax of December 14, 1990 (as of January 1, 2019)

29 Federal Act on the Harmonization of Direct Taxes of the Cantons and Municipalities of December 14, 1990 (as of January 1, 2019)

30 See Commentary on Swiss Tax Law, International Tax Law, Basel 2015, Art. 13 N 30.

31 See Commentary on Swiss Tax Law, International Tax Law, Basel 2015 Art. 13 N 31.

32 See Commentary on Swiss Tax Law, International Tax Law, Basel 2015 Art. 7 N 145 ff.

33 See Commentary on Swiss Tax Law, International Tax Law, Basel 2015 Art. 7 N 152.

34 See Commentary on Swiss Tax Law, International Tax Law, Basel 2015 Art. 7 N 154.

35 See Lang/Lüdicke/Reich, IStR 2008, 709-744.