Taxation of cryptocurrencies in private assets in Germany

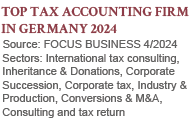

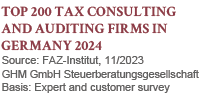

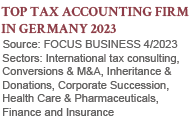

By Dr. Peter Happe, Tax Advisor/FB International Tax Law/C.P.A., Cologne and Munich.

Cryptocurrencies (Cryptos for short) have become established stores of value and means of payment and are used for “securitization” of investments in all possible asset classes such as equity in companies, loans, land, art, wine and even precious stones and vintage cars or rights of use (so-called tokenization). According to plausible estimates, the market value of cryptos such as Bitcoin has reached a volume of 2 trillion euros. Although the well-known cryptos such as Bitcoin and Ethereum account for the majority of these “currencies”, there are also around 9,000 other, mostly exotic cryptos and a large number of more or less reputable trading platforms on which the cryptos can be traded and stored on so-called wallets. A private exchange of cryptos is just as possible as storing them on so-called cold wallets in a safe or on a private computer at home. The number and volume of cryptos are constantly growing, as is the number of investors. There is a gold rush atmosphere and quite a few crypto investors have become millionaires, which is what makes investments in cryptos so attractive. Unlike the taxation of gold, the taxation of cryptos is a largely unknown legal territory, at least in Germany. This applies not only to civil law, but also to supervisory and tax law. This article only deals with the taxation of cryptos in private assets, which is to be stipulated by a current draft BMF letter.

1. Structure of the BMF letter and qualification of the cryptos

Around three and a half years after the Federal Ministry of Finance – BMF in Berlin issued a statement on the treatment of cryptos under the Value Added Tax Act – UStG (BMF of February 27, 2018, Value Added Tax Treatment of Bitcoin and other so-called virtual currencies; ECJ judgment of October 22, 2015, C-264/14, Hedquist, BStBl. I 2018, 316; according to which trading in cryptos is generally exempt from value added tax), Berlin decided to issue a statement in draft on the income tax treatment of cryptos, under which the BMF understands all blockchain-based tokens. The letter deals not only with privately held or traded cryptos, but also with commercially or professionally held cryptos. The uncertainty with this largely unregulated terrain is made clear by the fact that the BMF letter is preceded by a legend and defines terms such as mining, staking, token, blockchain.

In its draft letter, the BMF simply assumes that cryptos are non-depreciable, intangible assets such as rights, advantages, know-how or foreign currencies, and that in private assets they correspond to the so-called “other assets” of Section 23 (1) sentence 1 no. 2 EStG. Even if this view is not entirely undisputed, because it is questioned in practice whether they are taxable assets at all, one must concede that the asset status can hardly be doubted with justification (affirming also the FG Berlin-Brandenburg in the decision of June 20, 2019, 13 V 13100/19, more cautious, however, FG Nuremberg v. April 08, 2020 – 3 V 1239/19). Like all announcements by the tax authorities without the force of law, they initially only bind the tax authorities themselves.

If and to the extent that proceedings relating to the taxation of cryptos are pending before the tax courts on this and other topics, it is of course the highest duty of the advisor to join these proceedings by means of an objection and an application for suspension of the proceedings, so that the not infrequently surprising case law of the tax court has a positive effect on the crypto investor years later. Every acquisition or disposal of cryptos is a barter transaction. If and to the extent that less than twelve months lie between the acquisition and disposal (sale and exchange) of cryptos, the capital gains after offsetting with capital losses from cryptos in private assets are taxable from EUR 600. If cryptos are held for longer than 12 months, they can be sold tax-free in private assets. In the case of cryptos acquired on different acquisition dates, the taxpayer can optionally apply the Fifo simplification procedure, which is tax-favorable in the case of rising prices, according to which it is assumed that the cryptos acquired first per wallet are sold first, or he can provide individual proof of the disposal due to the clear identification of all cryptos.

2. Staking/Lending/Liquidity Mining/Yield Farming

According to the tax authorities, the tax-free disposal period automatically extends from 12 months to 10 years if income in the form of lending, staking, liquidity mining or yield farming is generated with the cryptos. This is because these activities are always associated with a fee, i.e. the cryptos are used to generate income within the meaning of Section 23 (1) sentence 1 no. 2 sentence 4 EStG. Here one can object that certain staking activities themselves represent an exchange that is tax-free if it took place after 12 months. The re-exchange after the end of the staking is possibly a separate acquisition process. Also, not all crypto holdings are infected equally. Especially in mining, there is a risk that the use of numerous computers will exceed the limit for commercial activity and the cryptos used and won cannot be sold tax-free at all because they have become business assets. For reasons of proof, the staking and lending holdings and the speculatively held holdings, with which only a capital gain is to be achieved, should be strictly separated from each other.

3. Losses from Cryptos

The high volatility of the prices, but also the large number of existing, partly superfluous cryptos without function almost inevitably lead to the fact that most crypto investors suffer not inconsiderable losses. Although crypto losses and gains in the same year can possibly also be offset against other private sales transactions. If a balance remains after that, it can be carried back one year or carried forward indefinitely and offset against other private capital gains. However, an offsetting with other income such as salary income or commercial activities is completely out of the question. Against this background, a commercial infection of cryptos by depositing them into business assets a sufficient time before the loss realization can make sense.

4. Emigration

Successful crypto investors have often accumulated considerable crypto values in their private assets through staking and can hardly wait to realize the profits and convert them into euros or dollars. However, they cannot do this tax-free before the end of ten years with residence in Germany, which is why a move to a low-tax foreign country such as Switzerland can be interesting, where such profits can be realized tax-free sooner. The German Foreign Tax Act has put a hurdle in the way in that when Germans move to DBA countries such as Switzerland, but also Italy, Singapore etc., in addition to off-shore countries without a DBA such as Panama, Paraguay, Chile, certain income is taxed subsequently in Germany for the year of emigration + 5 years (e.g. Switzerland) or +10 years (non-DBA countries) (§ 2 AStG). This applies, for example, to domestic or so-called non-foreign income. Foreign income, on the other hand, is not subsequently taxed in Germany. It is completely unclear whether crypto income is non-foreign or foreign income if it is held in private assets. If cryptos are issued, for example, by so-called digital Decentralized Autonomous Organizations – DAO, which are generally completely unregulated and have no legal domicile, there is considerable tax uncertainty as to who is the debtor of the cryptos. One could justifiably take the position that cryptos as so-called “other assets” are rights that would then not be taxable in Germany and could be sold tax-free. Alternatively, in such cases, definitive foreign assets can be created through structural measures, which is why there would no longer be a tax nexus to Germany.

4. Cryptos in inheritance and gift tax

The German Inheritance Tax Act, which is to be applied both to gratuitous transfers mortis causa or in the case of gifts, requires in principle a valuation on a cut-off date, which is regulated in § 9 ErbStG. § 12 ErbStG refers – except in special cases – in principle to the first part of the Valuation Act, i.e. §§ 1 to 16 BewG. As a valuation unit, in our opinion, the individual token is to be used, which is to be valued at the fair value, i.e. the market value of § 9 BewG, and not, for example, on the underlying, if an underlying such as art, land or even wine is tokenized by it. The difficulty is less the question of whether a bid or ask price is to be used as a basis on the valuation date. Here, every price can be justified, which is why, in our opinion, a mean price should be used. More interesting is the question of which market is to be used for the valuation. There are considerable price differences between the central markets (such as Binance or Coinbase) and decentralized markets (such as Uniswap), which is the reason why arbitrageurs are so successful at the moment. For income tax purposes, the tax authorities use the average price of several trading platforms. In connection with cryptos in business assets, the question is above all whether it is harmful administrative assets within the meaning of § 13b ErbStG or privileged assets, because it represents a claim in kind, especially in tokenization cases, which is why a commercial infection should be considered as a structuring measure of crypto assets for inheritance tax purposes. The German Inheritance Tax Act must also be observed in cases of emigration, because Germans always remain subject to subsequent taxation in Germany for 5 years after emigration in Germany.

5. Outlook

Obviously, there is also a considerable so-called structural enforcement deficit in the taxation of cryptos, because cryptos can be exchanged anonymously abroad or traded privately (as also the FG Baden-Württemberg, judgment of March 2, 2018, Az. 5 K 2508/17), without the tax authorities ever finding out about it. In fact, it can only theoretically trace the trading and transactions on the basis of billions of transactions daily, for which it already lacks the resources and the will.

The Federal Constitutional Court had recognized such a structural enforcement deficit in its landmark decision of March 9, 2004, 2 BvL 17/02 in a similar constellation in the taxation of securities in the years 1998 and 1999 within the meaning of § 23 para. 1 EStG a.F. as unconstitutional, because tax-honest and tax-dishonest taxpayers were taxed unequally. This ultimately led to the introduction of the withholding tax by the banks in 2009. The BMF has at least attempted to get a grip on the goings-on with regard to EU requirements with the draft Crypto Value Transfer Ordinance of May 11, 2021 for money laundering reasons. In a recently held hearing on the current BMF letter, a representative of the BMF stated that there is no enforcement deficit with regard to possible information requests to platform operators. In our opinion, this argument does not hold water, as a not inconsiderable and increasing proportion of transactions are processed via decentralized exchanges.

A considerable internationally coordinated effort is required to regulate and tax cryptos. Market participants at any rate assure that regulation and clear international regulations in taxation as well as the supervision of marketplaces would rather help than harm the growth of the market. A fundamental discussion of these open points, which have been presented in an insinuating manner, before the German tax courts is still pending, which is why a move to more tax-stable jurisdictions such as Switzerland is always advisable for larger assets, not only when investing in cryptos.