Swiss domestic assets in the inheritance tax treaty between Switzerland and Germany

By Dr. Peter Happe, Tax Advisor/Specialist in International Tax Law/C.P.A., Cologne and Munich, and

Lothar Boelsen, Certified Public Accountant/Lawyer/Tax Advisor, Frankfurt

The inheritance tax double taxation agreement between Switzerland and Germany1 (E-DBA) has some interesting positive and negative surprises in store, which are helpful to know and use in estate and relocation planning. This includes, above all, the fact that “Swiss domestic assets” are exempt from taxation in Germany in the event of the death of Swiss citizens.

The transfer of private and business assets to the next generation in the case of a so-called anticipated succession is, due to the far-reaching consequences over decades, a highly complex and emotional topic even in purely domestic matters, which can have costly consequences without the right advisors. In purely domestic matters, at least in Germany, the stability of tax legislation and thus planning security leaves something to be desired. A certain stability is at least guaranteed by the E-DBA, which has remained largely unchanged since 1978.

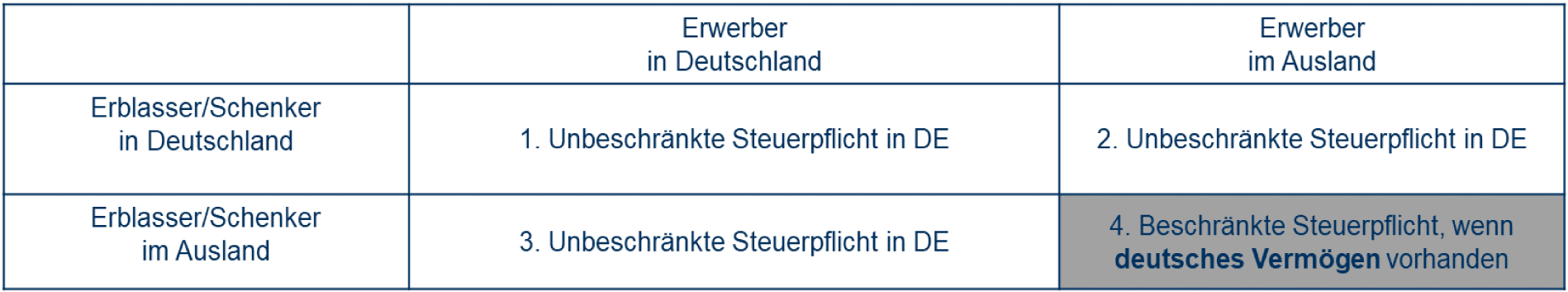

§ 2 Para. 2 No. 1 No. 1 and No. 2 ErbStG – disregarding E-DBA – leads to the following taxation consequences in Germany in the cross-border basic cases shown in the table, regardless of whether they are gifts or inheritances:

The records must provide an expert third party with a basic understanding of the value creation in the group of companies or in a uniform company of the business model and the function and risk profile of the transaction partners in a reasonable time. The functions handled with the individual related parties are to present an overview with regard to their type and the amount of the remuneration (so-called transaction overview).

The appropriateness documentation must document the serious effort that the arm’s length principle resulting from the economic and legal bases was correctly applied for the tax determination of income. The tax administration can question and verify the transfer pricing method used. The relevant point in time for the arm’s length comparison is generally the conclusion of the contract, if a contract was concluded, not the time of performance. The taxpayer can rely on arm’s length comparison data that became known subsequently. Also, planned data can possibly be used as a basis if they refer to already expired periods and on the basis of commercial, business management-based, cautious forecasts.

In addition, a master documentation must be prepared, which is also referred to as a master file, if the turnover limit of EUR 100 million is exceeded. Details can be found in §5 para. 2 Profit Allocation Recording Ordinance.

In the second main part of the Administrative Principles 2020, estimations and surcharges according to § 162 AO are finally treated, which affect the taxpayer as a so-called “spoiler of evidence” with the intention of skimming off the advantage from a lack of cooperation. For this purpose, the tax office may estimate. The basis of the estimation is to assume in an act of evaluating reasoning from the facts that comes closest to reality. The estimation results must be conclusive, economically possible and reasonable. Database studies are a permissible estimation method within the meaning of § 162 AO. For an income adjustment, defects in the justification of the appropriateness of transfer prices alone are not sufficient, but rather the transfer prices applied by the taxpayer must with a high probability not correspond to the arm’s length comparison and the transfer price determined by the tax authority must at least be more likely. If the authority estimates deliberately arbitrarily and to the detriment of the taxpayer, this can lead to the nullity of the estimation notice. In transfer pricing cases, an estimation according to § 162 AO should lead to taxation of the profit that would have been achieved if arm’s length prices had been applied.

The tax office can exhaust a range of estimated values to the detriment of the taxpayer.

If (a) the submitted records are essentially unusable or no records are submitted or (b) usable records for extraordinary business transactions have not been prepared promptly, a surcharge can also be imposed in addition to an estimation. The surcharge amounts to EUR 5,000; however, it should be at least 5%, but not more than 10% of the additional amount of income if an estimation had to be carried out. In the event of late submission of usable records, the surcharge amounts to up to EUR 1 million, but at least EUR 100 for each full day of exceeding the deadline.

The inheritance tax agreement with Switzerland is characterized above all by the fact that gifts are not regulated, but only transfers upon death. Therefore, in some cases it makes sense to plan the transfer upon death instead of making the transfer during one’s lifetime. For example, in the event of the death of a Swiss citizen residing in Germany (“tax domicile” within the meaning of Art. 4 Para. 1 and Para. 2 E-DBA), real estate assets located in Switzerland (often also referred to as “Swiss domestic assets”) are exempt from taxation in Germany according to Art. 10 Para. 1 Letter a) E-DBA. This so-called exemption procedure also applies if the heir is resident in Germany and is not a Swiss citizen. The basic case No. 1 in the table above is therefore restricted by the E-DBA through exemption in Germany. Not even the Swiss tax that may be incurred has to be credited, it remains with a progression proviso (also called Satzbestimmung in Swiss). If Swiss domestic assets are gifted by a Swiss citizen residing in Germany during their lifetime, this would be taxable in Germany according to the German taxation rules in § 2 Para. 1 No. 1 ErbStG as part of the worldwide assets within the meaning of basic case No. 1; the Swiss tax on the gift would only be credited. The tax on a gift during one’s lifetime would therefore be higher than the tax on a gift upon death, always assuming that the Swiss tax is lower than the German tax, which is only not the case in exceptional cases.

Swiss domestic assets are also exempt according to Art. 10 Para. 1 Letter a) E-DBA (exception to basic case 2.) if a Swiss citizen dies in Germany, but the heirs live abroad (e.g. in Switzerland or in a third country).

An exemption as an exception to basic case 3.) also applies if a testator with Swiss residence and Swiss citizenship at the time of death bequeaths Swiss domestic assets to German heirs (even without Swiss citizenship) upon death. This exemption results only very indirectly from the interplay of Art. 5 (location of the properties) and Art. 8 Para. 1 E-DBA, according to which assets may only be taxed in Switzerland if a testator with Swiss residence dies. Although one could come up with the idea that Germany may tax the German acquirer via Art. 8 Para. 2 E-DBA in conjunction with § 2 No. 1 ErbStG because they are resident in Germany. To realize the basic cases No. 3, Germany has had the fallback clause with Art. 8 Para. 2 E-DBA granted as an exception to the general E-DBA rule that inheritances are generally to be taxed in the state of residence of the testator. This exception is occasionally also referred to as overarching taxation. However, the Federal Fiscal Court recently confirmed in two BFH rulings2 that Germany may not tax Swiss domestic assets even in the case of German heirs – even without Swiss citizenship – and Swiss testators according to Art. 8 Para. 2 Sentence 3 in conjunction with Art. 10 Para. 1 Letter a) E-DBA. This was only recognized too late by the plaintiffs in the BFH rulings, which is why they did not get justice.

But that’s not all, because the exemption of Swiss assets goes even further: If a testator dies in Switzerland – with Swiss citizenship – and leaves behind, in addition to Swiss domestic assets (i.e. real estate in Switzerland), also Swiss permanent establishment assets, Swiss seagoing vessels and aircraft as well as “other assets” to the German heirs (with residence and permanent residence in Germany), Germany may not tax these assets according to Art. 8 Para. 2 Sentence 4 E-DBA if the heirs in Germany are also Swiss citizens (2nd exception to basic case 3. of the table above). Other assets include, for example, securities holdings, monetary assets and participation in corporations. Typically, the question of the application of this exception from taxation in Germany arises in cases in which Swiss descendants of a Swiss testator move to Germany. Then the question often arises whether the future inheritance should be transferred tax-free under Swiss tax law by way of anticipated succession before moving to Germany. From an inheritance tax perspective, there is no need for this according to the E-DBA, because the transfer upon death is tax-free in Germany. During the stay of the future heirs in Germany, gifts from Switzerland should in any case be avoided with a view to the inheritance tax-free solution, because the gift would always lead to taxes in Germany.

The basic case 4., limited tax liability, can usually be optimized in relation to Germany by interposing a corporation in Switzerland (so-called “blocker”), which holds the limited tax liability domestic assets within the meaning of § 121 BewG in Germany. The transfer of the shares in it is usually inheritance tax-free and also gift tax-free in Germany if the transferors and recipients of the transfer otherwise have no nexus to Germany.3

Despite all the joy about the exemption options, which are otherwise not customary in German E-DBA agreement practice, for asset transfers with a German connection, there are definitely disadvantageous provisions in the E-DBA with Switzerland, which can be regarded as unusual and aggravating compared to other E-DBAs that Germany has concluded. Thus, corresponding to the income tax DTA, Art. 4 Para. 3 E-DBA carries out an “overarching taxation” in such a way that in the event of a residence (“tax domicile”) of the testator in Switzerland and a “permanent home” in Germany for more than five years before the death, German inheritance tax is levied on the testator’s total assets. The Swiss tax is credited against the German tax. By reference to Art. 10 Para. 1 E-DBA in Art. 4 Para. 3 E-DBA, at least the real estate assets in Switzerland remain outside as “Swiss domestic assets” if the testator is a Swiss citizen. Nevertheless, the overarching taxation is an unpleasant and often overlooked taxation consequence of a residence in Germany if the permanent home is a professionally or frequently used apartment that is not only used for recreational, spa, study or sports purposes and is demonstrably only used occasionally. The hunting lodge of a Swiss hunting friend in the Black Forest should at least not lead to a permanent home in Germany if proof of only occasional use is successful.

Finally, the so-called “subsequent taxation” for a person moving from Germany to Switzerland according to Art. 4 Para. 3 E-DBA also leads to taxation in Germany if the person moving away dies in the year of departure or in one of the following five years and was subject to unlimited tax liability in Germany for 10 years before the departure. The Swiss right of taxation remains unaffected, i.e. Switzerland may tax with priority and Germany credits the Swiss tax. The subsequent taxation does not apply if the German person moving to Switzerland moves to Switzerland to take up employment, marries a Swiss citizen or was already a Swiss citizen at the time of departure. Regardless of this, Swiss domestic assets are also not taxed in Germany under the subsequent taxation, Art. 4 Para. 4 Sentence 3 E-DBA, which is attributed to Swiss citizens.

The preferential taxation for Swiss domestic assets must also be granted according to the clear wording at that point if a person has both Swiss and German citizenship. However, the German tax authorities like to see this somewhat differently in practice and try to apply subsequent taxation to German-Swiss dual citizens according to § 2 Para. 1 ErbStG or §§ 2 ff. AStG.

1 The agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Swiss Confederation in the field of estate and inheritance taxes of November 30, 1978, BGBl. II 1980, 595.

2 BFH of March 20, 2019, II R 61/15 and II R 62/15.

3 Reference to a possible German real estate transfer tax if the change of shareholders exceeds certain limits.