Exit taxation according to § 6 AStG n. F. – Initial experiences and the relationship to § 2 AStG or a plea for the abolition of exit taxation

By Dr. Peter Happe, Tax Advisor/FB Internat. Tax Law/C.P.A., Cologne,

Lothar Boelsen, WP/StB/RA, Frankfurt/Main

1. The changes to § 6 AStG in detail

With the ATADUmsG (BGBl. I 2021, 2035), § 6 AStG was significantly amended. § 6 AStG supplements § 17 EStG and is intended to ensure taxation before Germany loses the right to tax. § 6 AStG always applies when an emigrant,

- regardless of nationality,

- has been subject to unlimited tax liability in Germany for a total of 7 years of the last 12 years, and

- moves abroad and

- holds capital investments of 1% or more in domestic and foreign corporations in private assets.

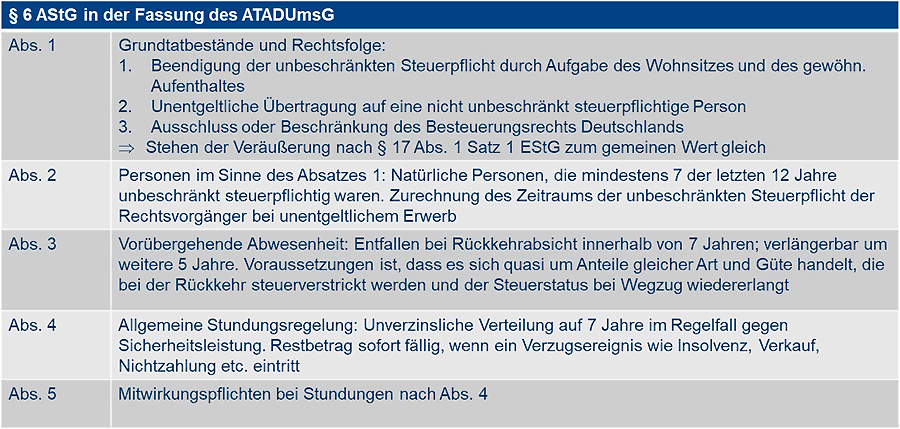

The exit tax is levied on the increase in value of shares in corporations, without the corporation itself having to relocate its registered office or management. The exit taxation serves to ensure the taxation of hidden reserves in shares in corporations quasi in the last second of the departure within the meaning of § 17 EStG, before Germany loses the right to tax to the future state of residence according to Art. 13 Para. 5 OECD-MA. In this case, the hidden reserves in the shares of the corporations are taxed as if the shares had been sold at fair market value (fictitious sale). This therefore also applies if the investment has accounted for 1% or more of the capital of the corporations in the last five years before the departure (§ 6 Para. 1 AStG). The holding period of the legal predecessor (donor or testator) is attributed to the emigrant (§ 6 Para. 2 AStG). Internationally, this tax is also referred to as “Exit-Tax”.

The most important changes to § 6 AStG are:

- The observation period is limited to 7 years of the last 12 years and no longer includes the last 10 of a lifelong period of the emigrant. This certainly represents a simplification, especially for people who are internationally mobile and move back and forth between Germany and abroad. The change makes the law more manageable for people who, for example, spent their childhood in Germany and work in Germany as expatriates decades later. Under the old law, these would have been subject to the tax after just one year of unlimited tax liability if they had lived in Germany for more than 10 years as children. There was no justification for taxing such people even before. However, people who intend to leave must now decide to leave tax-free three years earlier. According to our experience, investors are therefore leaving Germany faster because they do not want to fall into the case of the exit tax.

- The exit facts are streamlined to three facts. According to the explanatory memorandum to the law, this should not change anything in terms of substantive law. However, the elimination of the right to tax shares in corporations due to a new DBA, e.g. in the case of real estate companies such as the DBA-Spain 2013 according to § 6 Para. 1 Sentence 1 No. 3 EStG, should now explicitly lead to taxation as a so-called passive de-consolidation. This had already been decided in the past by the tax court (FG Cologne of March 28, 2019, 15 K 2159/19, nrkr, revision pending at the BFH under Az. I R 30/19; BMF v. 26.10.2018, BStBl. I 18, 1104), but has now become law as a precaution. The utmost caution is therefore required when negotiating and enacting new DBAs, such as the one soon to be concluded with Italy.

- The non-interest-bearing, unlimited deferral of tax for EU/EEA citizens to EU/EEA countries is abolished and the exit tax is set for every departure, regardless of the country. This represents a significant infringement of EU law, as will be explained further below. In return, the tax is distributed over seven years in seven equal installments upon departure, which can be revoked at any time if the tax revenue is at risk. According to the wording and the explanatory memorandum to the law, however, this should not happen because the provision of security for the deferral should be the rule. However, the provision of security does not really provide relief for the deferral, because, as the ECJ has already established in the DMC case, the provision of security in its economic effects means that the tax could just as easily be levied immediately (European Court of Justice, C-164/12, judgment of January 23, 2014, DStR 2014, 193). As a rule, the departure requires appropriate preventive countermeasures, which as a rule perpetuate taxation in Germany (cf. Happe/Stingl, Planned reform of exit taxation and precautionary defense strategies, PIStB 11/2020, p. 312).

- According to the wording of § 21 Para. 3 AStG, ongoing deferrals from old cases should not be revoked when the ATAD-UmsG comes into force. At the same time, however, the possibility of asserting reductions in value upon sale is also abolished in old cases for the future. This is also a potentially unconstitutional intervention.

- The tax “is waived” in the event of intent to return, whereby according to the explanatory memorandum to the law, a demonstration of the intent to return or professional reasons for an absence no longer matter (BT-Drs 19/28652, p. 49). According to the explanatory memorandum to the law, the mere intention to return and a sufficient probability are sufficient. According to the explanatory memorandum to the law, the financial effects of exit taxation should be reduced and mobility increased by deferring the tax (BT-Drs 19/28652, p. 47). In the first practical cases, however, this goal is thwarted by the administration because the tax should not be waived at the time of departure, as the wording and also the explanatory memorandum to the law imply with reference to a “deferral”, but only upon return. The tax authorities apparently tend to apply the apparently broadly accepted retroactive elimination of the tax claim in § 6 Para. 5 AStG a. F. (cf. Häck in F/W/B/S, § 6, Rz. 446, 95 supplementary delivery of April 2020, on the old version) now also for § 6 Para. 3 AStG n. F. Clarity should be provided by a BMF letter on this, which, according to reports, is in preparation. This would make the flexibility and mobility postulated in the explanatory memorandum to the law ad absurdum. Nevertheless, one must probably advise every emigrant to submit an inquiry to the tax office as to when the tax is waived and at the same time to submit the application for the tax to be waived to the tax office in any case as a precaution.

- Surprisingly, § 6 Para. 1 Sentence 5 AStG a. F. has been omitted, according to which, in the event of the sale of the shares, the increase in value taxed according to the provisions of § 6 AStG should no longer be credited in the event of the sale. This will be discussed below in connection with § 2 AStG.

2. Relationship of § 2 AStG to § 6 AStG

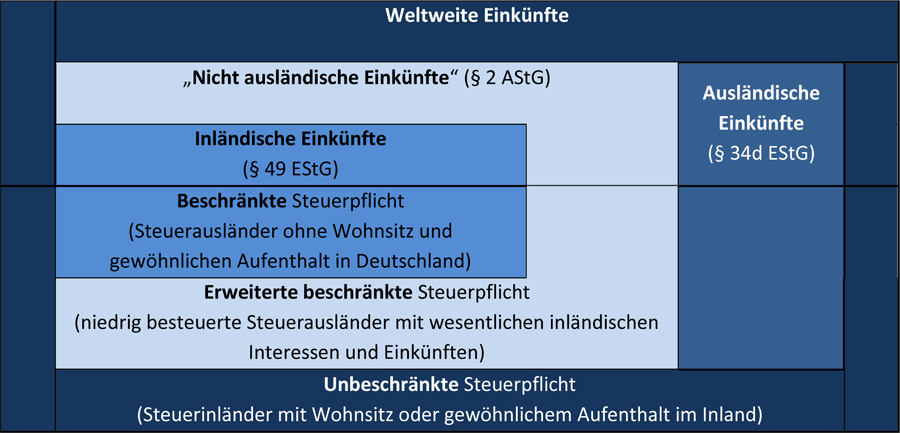

§ 2 AStG regulates the (subsequent) taxation of Germans who were subject to unlimited tax liability in five years out of ten years before the departure and move to foreign low-tax areas. If these persons still retain significant economic interests in Germany after the departure and domestic, so-called non-foreign income is generated, this income is subject to the so-called extended limited tax liability. This extended limited tax liability applies for a maximum of ten years after the end of the year in which the German left. If you leave on January 1, 2022, the non-foreign income could still be taxed in Germany until December 31, 2033. Unlike § 6 AStG, § 2 AStG only applies to German citizens.

§ 2 AStG is flanked by § 4 AStG, according to which the assets underlying the non-foreign income are subject to extended limited inheritance tax liability if Germans give away or bequeath the assets underlying the income. Consequently, a 10-year period also applies here. However, a prerequisite for the application of both the extended limited tax liability for income tax and for inheritance tax is that the income and assets are not subject to a foreign tax that corresponds to at least 30% of the German income or inheritance tax when applied to the income or assets.

In principle, a departure to foreign low-tax areas of DBA states could also fulfill the requirements of extended limited tax liability. In contrast to the other provisions of the AStG, such as in § 20 AStG, there is no so-called Treaty Override in § 2 AStG, so that as a rule only the income that is taxed in Germany according to a DBA is subject to German taxation. Nevertheless, when leaving for a DBA country, it must always be checked whether a DBA prevents the application of § 2 AStG or even contains an opening clause for the application. An opening clause for the application of § 2 AStG can be found, for example, in Art. 4 Para. 4 DBA-Switzerland for five years. § 2 AStG also applies to departures to non-DBA states such as Paraguay, Chile or Panama or for the so-called “Digital Nomads”, who do not become resident in any foreign territory.

Significant economic interests in Germany exist if, for example, one of the following conditions is met at the beginning of the assessment period (Nexus):

- Sole proprietorship in Germany,

- Participation in a partnership (as a limited partner, at least a 25% share of profits) in Germany,

- Participation in a domestic corporation within the meaning of § 17 EStG, i.e. the taxpayer or his legal predecessor had ≥ 1% of a corporation within the 5 years at the beginning of the assessment period, even if the participation is ˂ 1% at the time of the sale,

- the “non-foreign income” amounts to 30% of the total income or ≥ EUR 62,000 in the year of departure or

- Assets whose income non-foreign income as defined below, exceeds more than 30% of the total assets or > EUR 154,000.

According to today’s value ratios, a rented student apartment regularly leads to significant economic interests in Germany. By interposing a foreign corporation, the emigrant can neither avoid the aforementioned requirements nor the attribution of non-foreign income in Germany, since these so-called interposed companies are looked through (§ 2 Para. 4 AStG in conjunction with § 5 AStG).

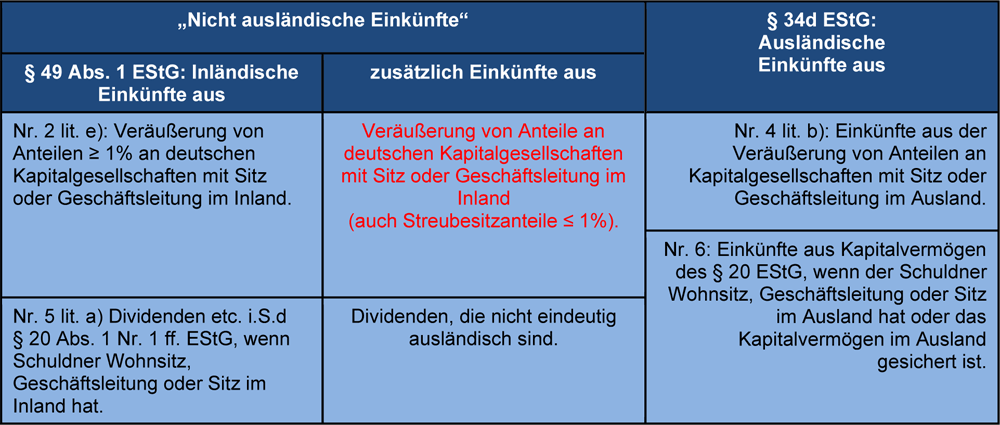

The non-foreign income is a category not mentioned in the law and includes, in addition to the enumeratively mentioned domestic income of § 49 EStG, all income that cannot be clearly attributed to the also enumeratively mentioned foreign income of § 34d EStG:

In connection with shares in corporations, it is noticeable that the non-foreign income with extended limited tax liability includes not only shares in domestic corporations ≥ 1% within the meaning of § 49 Para. 1 No. 2 lit. b) EStG, but also capital gains on non-foreign corporations. This results from § 34 No. 4 lit. b) bb) EStG, according to which profits from the sale of corporations with their registered office or management abroad are to be included in foreign income. Since a participation threshold is not mentioned in § 34 No. 4 lit. b) bb) EStG, all shares in foreign corporations (registered office or management abroad) initially count as foreign income, regardless of whether they are < 1% or ≥ 1%. Consequently, already from the reverse conclusion to § 34 No. 4 lit. b) bb) EStG, free float shares, e.g. domestic corporations in Germany, are taxable as non-foreign income. However, the same result is also achieved if one considers § 34d No. 6 EStG: Income within the meaning of § 20 EStG counts as foreign income if the debtor has its registered office or management abroad. Capital gains from shares of foreign corporations within the meaning of § 20 Para. 2 No. 1 EStG would therefore be foreign income. Capital gains from shares within the meaning of § 20 Para. 2 No. 1 EStG of domestic corporations would be taxable in Germany as non-foreign income. The same applies, in our opinion, to dividends from non-foreign shares, see the table below. This alone should be surprising for most emigrants.

The distinction between domestic and foreign corporations is clear when both the registered office and the management are located in Germany (then domestic income and at the same time non-foreign income) or the registered office and the management are located abroad (then clearly foreign income). However, the distinction is not so clear if the registered office is in Germany and the management is abroad (and vice versa); then the capital gains count as non-foreign income and could be taxed in Germany after the departure to low-taxed areas.

However, § 2 AStG has another surprise in store, which is probably unconstitutional and violates EU law: If emigrants sell shares ≥ 1% in “non-foreign” corporations, these capital gains will be taxable in Germany. This also applies if these shares were already taxed upon departure in accordance with § 6 AStG. The following sentence could still be found in § 6 Para. 1 Sentence 5 AStG a. F. (see also R 49.1 Para. 4 EStR 2021):

“Sections 17 and 49 Para. 1 No. 2 Letter e of the Income Tax Act remain unaffected with the proviso that the profit to be assessed under these provisions from the sale of these shares is to be reduced by the increase in assets taxed under the above provisions.” ”

This sentence has been tacitly and – as far as can be seen – without justification omitted with the ATAD-UmsG. The legal consequence is therefore that the increase in value of shares in non-foreign corporations of emigrants to low-taxed areas is to be taxed twice. Firstly upon departure, and secondly upon later sale.

Example: The German taxpayer A moves from Stuttgart to Panama in 2022, giving up unlimited tax liability. He holds shares in domestic and foreign corporations in a Swiss deposit. The increase in value of shares amounting to 5% in a family corporation on the Swabian Alp is taxed upon departure (increase in value taxation according to § 6 AStG with around 28.5%). In 2025, A, still living in Panama, decides to sell all shares to his siblings because he has other plans for his life. The sale is taxed again in Germany in accordance with § 2 AStG because it does not involve profits from shares in foreign corporations within the meaning of § 34d EStG. There is no longer any crediting of the exit tax in accordance with § 6 AStG. His share sales and dividends from domestic shares (free float shares < 1%) in the Swiss deposit are taxable in Germany at least until the end of 2025 due to the still existing nexus.

Not only can there be an unconstitutional double taxation of the increase in value by §§ 2 and 6 AStG. The application of § 2 AStG is likely to be unconstitutional due to a so-called structural enforcement deficit. This is because the tax authorities are only likely to learn of non-foreign income in rare cases, especially if it involves income from listed shares in German corporations in foreign deposits and the deposit holder is not listed as a German taxpayer. The Federal Constitutional Court recognized a structural enforcement deficit in its decision of March 9, 2004, 2 BvL 17/02 in a similar constellation in the taxation of securities in Germany in the years 1998 and 1999 within the meaning of § 23 Para. 1 EStG a.F. as unconstitutional because honest and dishonest taxpayers were taxed unequally.

3. Overview of the legal consequences of § 6 AStG n. F.

The ATAD-UmsG, which implements the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive 2016/1164 of July 12, 2016 (Anti Tax Avoidance Directive), as amended by EU Directive 2017/952 of May 29, 2017, amended, among other things, Section 6 AStG as described above. According to the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive, member states must legally implement mandatory measures to prevent international tax avoidance. By embedding the amendments to Section 6 AStG in the ATAD-UmsG, the legislator apparently only wanted to suggest that it was obliged to tighten the exit tax under European law. But that is not the case. The EU Directive does not provide for its introduction at all. Other EU countries such as Austria, Italy or Croatia do not have any tax offenses comparable to Section 6 AStG.

The ATAD Directive was therefore only a guise for tightening the exit tax. In the explanatory memorandum to the law (BT-Drs 19/28652, p. 49), the legislator’s concern is very clearly expressed that it would have to allow the deferral regulations for relocations to third countries such as Switzerland. The European Court of Justice, following a submission by the Baden-Württemberg Tax Court, considered the deferral regulation of Section 6 (5) AStG a. F. to be incompatible with European law insofar as the provision contradicts the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons between Switzerland and the EU (submission decision of the Baden-Württemberg Tax Court of June 14, 2017, 2 K 2413/15; Ref. ECJ C-581/17, Rs. Martin Wächtler against Finanzamt Konstanz; cf. Wilke, PIStB 2019, p. 291). Instead of applying the ECJ ruling, as it would have been obliged to do, the BMF initially issued a non-application decree on November 13, 2019 and only granted emigrants payment in installments (BStBl. I 2019, 1212). This deferral has since been classified as illegal by two courts (FG Baden-Württemberg, court order of August 31, 2020, 2 K 835/19, EFG 2021, 20, nrkr.; BFH, Ref. I R 35/20; FG Cologne, decision of May 11, 2021, 2 V 1929/20).

Knowing full well that it must ultimately equate relocation to Switzerland with relocation to EU/EEA countries, the legislator very deliberately decided to abolish the general deferral rules for EU/EEA citizens when moving to EU/EEA countries. This means that relocation to Switzerland is no longer discriminated against, but relocation to EU countries is. The only alleged justification under EU law is a reference to more recent EU case law, because the ECJ had deemed a deferral and interest for the transfer of assets in the business sector (contribution of shares in a partnership, ECJ judgment of January 31, 2014, C-164/12, Rs. DMC; Transfer of assets to a foreign permanent establishment ECJ judgment of May 21, 2015, C-657/13, Rs. Verder LabTec) or business relocation (ECJ of November 29, 2011, C-371/10, Rs. National Grid) to be permissible. The ECJ judgment of December 21, 2016, C-503/14 cited by the legislator is, for example, completely unsuitable as justification because it regards the taxation of the increase in value in Portugal as a violation of the freedom of establishment. In the end, the legislator reverses course and restores the situation before 2007, which was already considered illegal under EU law at that time. The exit tax as it currently applies again was considered a violation of the fundamental freedoms (here freedom of establishment) (ECJ judgment of March 11, 2004, C-9/02, Rs. Hughes de Lasteyrie du Saillant); this legal situation has now simply been restored.

You have to stretch your mind considerably to find a constitutional justification for taxing emigration at all. After emigration, the emigrant no longer makes use of any state benefits that would justify taxation of the emigration base, because, by definition, he is generally no longer subject to unlimited tax liability and/or resident in the country of immigration. In addition, only unrealized and therefore supposed hidden reserves in the shares of corporations are taxed. As a rule, these can only be estimated values, which is only inadequately concealed by the term “tax base”. There is no inflow of payment to cover the tax payment at all. This at least violates the taxation according to ability to pay required under constitutional law. This applies in cases of temporary emigration even if the tax is not deferred as intended by the legislator, but only “ceases” upon return.

Furthermore, the exit tax, especially as it is designed in the future, leads to the fact that the country of immigration can regularly tax less if the country of immigration has to apply the taxed exit value as the entry value (e.g. Art. 13 para. 5 DBA-CH and Art. 13 para. 6 DBA-USA and Art. 13 para. 6 sentence 1 German basis for negotiation). For the emigrant, the emigration becomes a nasty surprise if the country of immigration has not agreed on such a DBA clause with Germany or if he moves to a non-DBA country: Here, the “tax base” is taxed again in the event of a sale. Due to the elimination of the depreciation clause of Section 6 (6) AStG a. F. by the ATAD-UmsG, the estimated exit value in Germany remains taxed, even though the value of the shares has not developed as estimated. The depreciation clause at least ensured that in the end only the value that is realized is taxed. Without a depreciation clause, there is no taxation according to ability to pay.

If, as described above, Section 2 AStG is to be applied to the shares at the same time and the capital gain is taxed again for non-foreign corporations without crediting the capital gains tax pursuant to Section 6 AStG, there is no constitutional justification for this.

Occasionally, it is argued to justify the exit tax that the emigrant has created values in Germany through the deduction of business expenses, which are realized abroad. This argument fails to recognize that in the case of the shares of Section 17 EStG, no tax-reducing acquisitions were made. This argument only takes effect at the level of the corporation itself, not for the taxation of the shares. The emigration of the domestic corporation itself is, however, also taxed in accordance with Section 12 KStG, the emigration of individual assets of the corporation in accordance with Section 4 (1) sentence 3 EStG and the transfer of so-called transfer packages and intangible assets abroad in accordance with Section 1 (3b), Section 1a AStG, at least taking into account a price adjustment clause. Especially in emigration cases, the disadvantage of a corporation becomes apparent, namely the doubling of the hidden reserves and the company value in the shares and in the corporation. If the shareholder and the domestic company move abroad, the same company value is even taxed twice upon emigration. This is not the only reason why the partnership is often the preferred legal form in international tax law.

The exit tax also shoots far beyond the target if, for example, in the case of real estate companies, Germany does not have the right to tax at all or does not lose it in the event of emigration, but the exit tax is to be applied according to the wording of Section 6 AStG. This is the case, for example, with real estate companies. In newer DBAs such as with the USA (Art. 14 para. 2 lit. a) DBA-USA), shares in corporations whose gross assets consist predominantly of real estate assets in the non-resident state are taxed in the state where they are located. In our opinion, the wording of Section 6 AStG would have to be reduced teleologically for emigration cases for shares with predominantly American real estate. However, it is at least questionable whether the tax authorities and tax jurisdiction would follow.

In the reverse case, that shares in German real estate corporations with predominantly domestic real estate assets are transferred abroad, the case law (FG Cologne of March 28, 19, 15 K 2159/15, nrkr., BFH pending under I R 30/19) applies the exit tax. In the case in question, the German father had transferred shares within the meaning of Section 17 EStG in a German real estate corporation to his son for partial consideration. The FG Cologne does not want to reduce the wording of Section 6 AStG a. F. teleologically, because the legislator certainly not only saw and accepted such cases, but it is not apparent how the restructuring of the assets at the corporate level should be taxed if not by applying Section 6 AStG. This reasoning leaves the reader puzzled, because in our opinion the restructuring of the German real estate of a corporation with its registered office and management in Germany is taxed in accordance with Section 1 KStG. Every restructuring of the German assets of a German corporation is taxed in Germany. In our opinion, Section 6 AStG is not required as an abuse prevention provision, especially since the shares in Germany also remain taxable in Germany. One can be curious about the judgment of the BFH in the matter.

In the judgment of the FG Cologne of February 28, 2019, something else clearly emerges, which still applies after the amendment of Section 6 AStG: In the case of gratuitous transfers of shares in corporations, there are no excessive income tax effects as mentioned above, but it is also a taxable transaction within the meaning of Section 3, Section 7 ErbStG. The gratuitous transfer is, if it is not a privileged transaction, e.g. within the meaning of Sections 13a, 13b and 13c ErbStG, also subject to gift tax and the exit tax with all the aforementioned negative income tax effects is to be applied (so-called substitute offense in Section 6 (1) No. 2 AStG n. F.). The donation of shares in corporations abroad thus leads to double taxation with exit tax and gift tax. In the case of correspondingly non-privileged assets and unfavorable tax brackets, taxation in Germany can quickly rise to over 60% and more of the “tax base”, namely from just under 30% income tax on the increase in value of the shares and 30% gift tax. This applies, for example, if foreign shares in corporations are not privileged at all because they are not EU/EEA companies. If the foreign country does not credit the gift tax (e.g. Canada due to lack of gift tax) or does not accept the donation as such, for example because the donation was subject to revocation (e.g. USA), the negative effects of the exit tax are multiplied many times over. Here again the reference that the domestic assets of domestic corporations are at least still subject to taxation. The EU-illegal and unconstitutional effects are intensified if the shareholder has to realize corporate assets at the level of the corporation in order to be able to pay the taxes at the private level. Not too long ago, the Federal Constitutional Court stated that it considers the gift tax exemption regulations in Sections 13a, 13b ErbStG for the preservation of companies, their liquidity and jobs not only to be in conformity with the constitution, but even to be required (Federal Constitutional Court, judgment of December 17, 2014, 1-BvL-21/12, BStBl. II 2015, 50). It is doubtful whether it would consider the present constellation to be in conformity with the constitution.

In our opinion, the legislator apparently also deliberately accepts the EU illegality for the freedom of movement of persons with the new standard, which is why we dare to predict that this law will be amended again in a few years. After all, even the explanatory memorandum to the law cannot conceal the fact that Section 6 AStG n. F. represents a considerable obstacle to emigration that is illegal under European law and an excessive taxation under constitutional law for entrepreneurs.