Exit taxation according to § 6 AStG – planned revision by the ATAD 2 Implementation Act and defense strategies

By Dr. Peter Happe, Tax Advisor/FB Internat. Tax Law/C.P.A., Cologne,

Dr. Michael Stingl, Attorney at Law, Munich

Moving from Germany without careful planning and tax considerations can quickly become a nightmare. Germany has placed small and large tax hurdles in the way of individuals leaving the country, which should at least be roughly known and should not be overcome without tax advice and not too short. One of the most important is the taxation of the increase in value in shares in corporations according to § 6 AStG when moving away

1. Overview of § 6 AStG

§ 6 AStG supplements § 17 EStG and ensures taxation before Germany loses the right to tax. According to de lege lata, § 6 AStG always applies if a person leaving the country – regardless of nationality – who has been subject to unlimited tax liability in Germany for a total of 10 years during his or her lifetime, moves abroad and holds capital investments of 1% or more in domestic and foreign corporations in his or her private assets. The exit tax is levied without the corporation having to relocate its registered office or management. The exit taxation serves to ensure the taxation of hidden reserves in shares in corporations quasi in the last second of the departure within the meaning of § 17 EStG, before Germany loses the right to tax to the future state of residence pursuant to Art. 13 para. 5 OECD-MA. In this case, the hidden reserves in the shares of the corporations are taxed as if the shares had been sold at fair market value (fictitious sale) if the investment on the day of departure or in the last five years before departure amounts to 1% or more of the capital of the corporations (§ 6 para. 1 AStG).1 The holding period of the legal predecessor (donor or testator) is attributed to the departing person (§ 6 para. 2 AStG).

In accordance with the purpose of this standard, circumventions of the taxation of such capital shares in Germany are prevented by moving to another country. In addition, other transfers of shares abroad through donations, inheritances, conversions, contributions to a foreign permanent establishment or the like are also taxed.2 Above all, the law not only refers to the abandonment of the place of residence or habitual abode and thus the termination of unlimited tax liability under domestic German tax law, but also, without terminating unlimited tax liability, to the establishment of a place of residence or habitual abode abroad, on the basis of which the taxpayer becomes resident abroad (Art. 4 OECD-MA). If there is a residence abroad, unlimited tax liability in Germany remains in principle if a residence and a permanent residence in Germany remain. Despite having a residence and habitual abode in Germany, § 6 AStG can then trigger taxation of the disclosed and hidden reserves in shares in corporations if the residence is moved abroad. This is the case, for example, if, in the case of a further residence abroad, the center of vital interests is established there within the meaning of Art. 4 para. 2 lit. b) OECD-MA.

Even if the exit taxation with the income tax “only” leads to a taxation of the determined capital gain as the difference between the fair market value of the shares and the acquisition costs to 60% according to the partial income procedure in § 3 No. 40 letter c) EStG at the individual tax rate of at least up to 47.5% (including solidarity surcharge) plus, if applicable, church tax of 8-9% (in total about 30% of the fictitious capital gain), the taxation without a cash inflow from the sale of the investment is a real obstacle to departure. In addition, exit taxation can certainly lead to double or multiple taxation with German and foreign income tax as well as inheritance and gift tax, as the following example shows.

Example: The entrepreneur U, who has lived in Cologne all his life (unlimited tax liability and residence in Germany), dies and leaves his son S, who stayed in Switzerland after studying in St. Gallen and is resident in Zug, the shares in GmbH G, the Aktiengesellschaft A in Zurich and the LLC L (a corporation) in Jersey, USA. U held 25% or more of the capital in all companies. The companies G and A have a positive enterprise value at the time of death, the company L has a negative value.

Due to the death, the shares are transferred to a Swiss taxpayer and German income tax is levied on all shares in corporations as if they had been sold. According to a recent ruling by the BFH, the negative enterprise value of L may not be deducted from the positive enterprise values G and A or offset against other income.3 In addition, German inheritance tax is payable. In addition to this double taxation in Germany, it must be examined whether US tax is also incurred, which would be the case, for example, if the father is a US citizen by birth.

If the father U had acquired the shares of G GmbH before 1999, it would have been possible to additionally check which part of the increase in value is tax-free. Increases in value that had already occurred before 1999 were due to the change in the tax-free participation rates of ≤ 25% to last ˂1% (until 2009) tax-free until the change of the participation rates in §§ 17 EStG, 6 AStG. The part of the increase in value that arose in the period after 1998 is taxable.4 Due to the extension of the exit taxation to foreign corporations in 2006, one could at least ask the question whether it is constitutional that also increases in value until 2006 in foreign corporate shares are subject to the exit taxation.

As an exception, on request, if there is a credible intention to return to Germany within five years (extendable by another five years) when leaving the country and the tax office is notified immediately, taxation is initially waived (§ 6 para. 3 AStG).5 In addition, in the event of departure within the EU or the EEA, a reduction in value that occurs when the shares are sold and is not taken into account in the country of immigration and is not due to a distribution-related reduction in value can be taken into account (§ 6 para. 6 AStG). The tax due can be paid in five interest-bearing installments upon application against the provision of security if the immediate levy constitutes a considerable hardship (hardship clause in § 6 para. 4 AStG), or upon application pursuant to § 6 para. 3 AStG for five or ten years against the provision of security. The deferral is to be revoked if the shares are sold or the company is liquidated. If the value of the shares falls after the departure, this is generally irrelevant for German taxation in a non-EU/EEA country.

In the case of a departure within the EU and the EEA, citizens of an EU or EEA country are granted an interest-free deferral without the provision of security (§ 6 para. 5 AStG). It is at least gratifying that the European Court of Justice, following a submission by the Baden-Württemberg Tax Court, considers the regulation of § 6 para. 5 AStG to be contrary to European law insofar as the standard contradicts the Free Movement Agreement between Switzerland and the EU (referral decision of the Baden-Württemberg Tax Court of June 14, 2017, 2 K 2413/15; Ref. EuGH C-581/17, Rs. Martin Wächtler against Finanzamt Konstanz).6 This does not achieve income tax exemption for leaving the country to Switzerland, but the tax would be permanently deferred as in the case of leaving the country to an EU/EEA country without collateral and interest. As a result, those leaving the country to Switzerland should also benefit from the regulation of § 6 para. 6 AStG, according to which the tax assessed but not levied in the event of departure to Switzerland is to be reduced if it turns out that the value originally set in Germany for the exit taxation is too high in the event of a later sale or liquidation of the company. However, those leaving the country to Switzerland cannot enjoy this for long because an abolition is generally abolished when leaving the country, even within the EU/EEA.

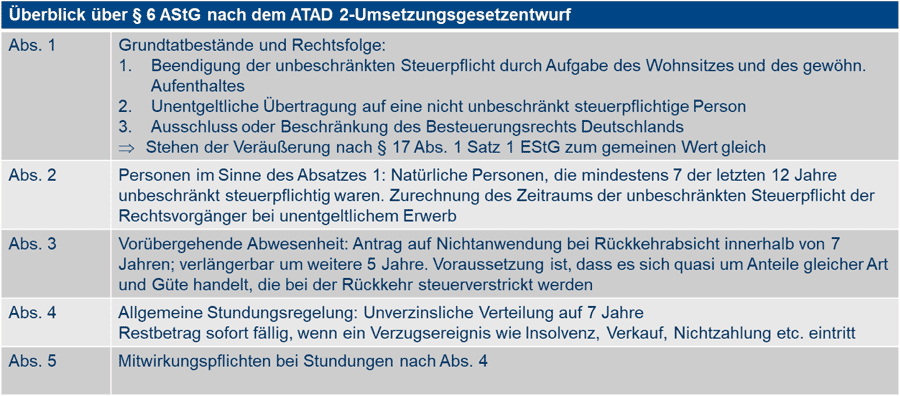

2. Amendments by the ATAD Implementation Act in the draft

With the draft bill dated December 10, 2019 of a law to implement EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive 2016/1164 of July 12, 2016 (Anti Tax Avoidance Directive), amended by EU Directive 2017/952 of May 29, 2017, the Member States must legally implement mandatory measures to prevent international tax avoidance. The three most important measures of the law, which is still to come into force in 2020, are:

- The observation period is limited to 7 years of the last 12 years and no longer includes the last 10 of a lifelong period of the departing person, which is certainly a simplification especially for people who are internationally mobile and move back and forth between Germany and abroad. However, people who intend to leave the country must decide to leave the country tax-free three years earlier.

- The interest-free, unlimited deferral of tax when leaving the country to the EU/EEA countries and Switzerland will be abolished.7 Instead, a distribution of the tax on the departure over seven years is introduced, which can be revoked at any time if the tax revenue is at risk. According to the wording of § 21 AStG-E, ongoing deferrals from old cases should not be revoked when the ATAD-UmsG comes into force.8 At the same time, however, the possibility of asserting reductions in value upon sale will also be abolished in old cases for the future. It may therefore be necessary to consider realizing the losses in value by selling the shares before the planned entry into force of the ATAD Implementation Act if the law should not come into force in 2020.

- The intention to return must already be made credible to the tax office at the time of departure.

Since exit taxation is being introduced throughout the EU, exit taxation will always occur when moving from these countries in the future, which is why the immigration value, which may only be determined in accordance with § 17 para. 2 sentence 3 EStG if a comparable taxation such as in § 6 AStG has taken place abroad, will become considerably more important.

3. Design options to avoid exit taxation

Participation in commercial sole proprietorships or (originally commercial) partnerships in Germany and abroad is not subject to exit taxation in Germany, provided that the permanent establishments within the meaning of § 12 AO or Art. 5, 7 OECD-MA in Germany are retained and neither individual economic goods9 nor the entire business are transferred abroad10. Thus, a move by co-entrepreneurs, i.e. partners of commercial or freelance partnerships or commercial or freelance sole proprietors, is harmless if they do not take any economic goods across the border (tax detachment).11

The preceding explanations result in some design options for avoiding exit taxation pursuant to § 6 AStG12, also after the amendments by the ATAD Implementation Act as probate means for preventing exit taxation are:

- Residence management: 13In the event of a planned departure, the residence in Germany should not be abandoned or moved abroad without careful consideration without taking one of the measures described below. Likewise, no residence should be established in Switzerland while maintaining German unlimited tax liability, because this already triggers exit taxation. This means that in the case of a second residence in Switzerland, the habitual abode in Germany and also the closer personal relationships within the meaning of Art. 4 para. 2 OECD-MA should remain.

- Conversion of a domestic corporation into an originally commercially active GmbH & Co. KG: By converting, only the disclosed taxed reserves at the level of the shareholder are subjected to taxation as profit distributions, but not the hidden reserves at the level of the corporation. In addition, the book values can be transferred in a tax-neutral manner, i.e. unlike when leaving the country, the shares are not subject to a fictitious liquidation of all hidden reserves including goodwill. The silent companies at the level of the corporation remain in the business assets of the co-entrepreneurship for taxation in Germany, which is why taxation is not considered when leaving the country. However, it should be noted that after a conversion, the shares are subject to a blocking period of five years pursuant to § 18 para. 3 UmwStG with regard to trade tax.14

- Hidden contribution of the shares in an originally commercial GmbH & Co. KG within the meaning of § 15 para. 1 sentence 1 EStG: It is crucial that the shares are also functionally assigned to the permanent establishment, which is only the case if the shares serve to fulfill the commercial permanent establishment function and thus become business assets15 Shares in an asset-managing GmbH & Co. KG are just as little protected from exit taxation as shares in an originally commercial GmbH & Co. KG, which, however, do not serve the originally commercial permanent establishment function; they are considered private assets. The usual designs in the past of contributing shares in corporations to commercially shaped or so-called upwardly infected16 German partnerships within the meaning of § 15 para. 3 EStG are no longer recommendable designs after a change in case law and legislation.17 This is because the Federal Fiscal Court had ruled that only original commercial partnerships and not commercially shaped or infected partnerships establish a permanent establishment in Germany under the DBA.18 Commercial infection and shaping are legal institutions unknown in DBA law, which is why only original commercial partnerships can establish a permanent establishment. In addition, the shares must then be assigned to the permanent establishment according to a causal connection.19 In any case, the shares must be functionally assigned to the permanent establishment pursuant to Art. 10 para. 4 OECD-MA. This should at least be the case for managing holding permanent establishments if they hold at least two investments.20

- Lateral infection in the sense of enriching an asset-managing GmbH & Co. KG, which holds capital stock investments or into which capital stock investments are invested, into an originally commercial GmbH & Co. KG through a commercial activity within the meaning of § 15 para. 1 No. 1 EStG: An asset-managing GmbH & Co. KG, which holds domestic and foreign investments in corporations without being commercially active, does not shield – like commercially shaped corporations – from exit taxation. If necessary, these companies can be assigned active management functions, so that it is a managing holding, which only succeeds with at least two investments, see above. Whether an infection by a commercial activity is sufficient and whether the shares are functionally related to the activity of the commercial permanent establishment function is a question of fact and should be accompanied by a binding information in case of doubt.

- Sale of shares with right of repurchase21. The purchase price decreases depending on the age of the seller due to the reserved usufruct significantly below the market value of the shares. Upon return, the sale is reversed suspensively or the shares are repurchased.

- Gratuitous transfer of the shares u. U. gift tax-free to a natural person or a domestic foundation, if necessary, under usufruct reservation22and u. U. combined with a right of withdrawal from the donation upon return to Germany. The narrow requirements of §§ 13a, 13b ErbStG as well as the income tax consequences of a must be taken into account and examined in detail.

- Participation as an atypical silent partner in a domestic corporation:23By participating in the atypical silent partnership, a co-entrepreneurship is created, in which the GmbH as the owner of the commercial business and the partner with the intention to leave the country are involved. The shares in the domestic corporation, which are attributable to the atypical silent partner at the GmbH, then count as the necessary special operating assets II of the atypical silent partnership24, which is why the shares remain tax-liable in Germany in the event of departure.

- Granting of call options: It is occasionally recommended that relocating persons have call options granted to them instead of shares in domestic and foreign corporations. Until exercised, the call options would not be considered shares within the meaning of Section 6 (1) sentence AStG in conjunction with Section 17 (1) sentence 1 EStG. A call option on more than 1% of shares in a corporation could be subject to exit taxation as a so-called “expectancy” within the meaning of Section 17 (1) sentence 3 EStG, even if no beneficial ownership is transferred before the call option is exercised. However, the wording of Section 6 (1) sentence 1 EStG, which only refers to shares within the meaning of Section 17 (1) sentence 1 EStG and not to the expectancies regulated in Section 17 (1) sentence 3 EStG, speaks against this25. In contrast, however, the Schleswig Holstein Tax Court, in its non-appealable ruling of September 12, 2019, considered an expectancy within the meaning of Section 17 (1) sentence 3 EStG on hidden reserves in the shares to be sufficient for taxation under Section 6 AStG. In the case decided, the relocating person had lent his shares by way of a securities loan, whereby the transfer of beneficial ownership had been effectively completed before the relocation without disclosing hidden reserves; however, the claim for return from the loan agreement should be regarded as an expectancy within the meaning of Section 17 (1) sentence 3 EStG, which is to be taxed at the time of relocation.26

With all structuring options, it must be accepted that the shares in Germany not only remain subject to income tax, but also to inheritance tax. Therefore, one should consider whether the entrepreneurial holdings in corporations should not be parked early on in a foreign foundation upon formation or immigration.

1It must also be examined in principle whether the fictitious disposal under Section 6 AStG triggers a disposal within the meaning of the subsequent taxation provisions of Section 13a (5) ErbStG (denying this, Troll/Gebel/Jülicher, § 13a, marginal note 178).

2The relocation or conversion of a domestic corporation fails due to the exit rules for corporations such as in Section 17 (5) EStG and Section 12 KStG; see Schmidt, PIStB 2013, p. 41 and p. 76.

3See BFH ruling of April 26, 2017, I R 27/15, DStR 2017, 1913. Among other things, the possibilities of loss utilization in corporation shares upon relocation, Kraft/Gräfe, IWB 2016, 384.

4See decision of the BVerfG of July 7, 2010, 2 BvR 748/05, BStBl. II 2011,16.

5Judgment of the Münster Tax Court of October 31, 2019, 1 K 3448/17 E, nrkr; BFH, file number I 55/19.

6See Wilke, PIStB 2019, p. 291.

7So far, this was still considered a violation of the freedom of establishment according to ECJ ruling of March 11, 2004, case C-9/02.

8See Heurung/Ferdinand/Kremer, IStR 2020, p. 94.

9Section 4 (1) sentence 4 EStG, possibly favored according to Section 4g EStG; Section 6 (5) sentence 1 EStG; Section 12 (1) KStG.

<10Section 16 (3a) EStG. Relocation possibly favored according to Section 36 (5) EStG.

11According to Section 1 (3) sentences 9 to 12 AStG, the transfer of functions, business opportunities and intangible assets, such as know-how and a customer base, and their use abroad is also fiscally detrimental.

12See Kleine/Rippert, IStR 2019, 439.

13See Häck in Flick/Wassermeyer/Baumhoff/Schönfeld, AStG, status May 2020, § 6, marginal note. 171.

14A similar direction is taken by the proposal to hold only an atypical silent participation in a German corporation in the event of an intention to relocate. See Bron, IStR 2016, 26. In the Germany-Switzerland relationship, however, an atypical silent partnership triggers high withholding taxes in Germany.

15See Wassermeyer in Wassermeyer, DBA, status Dec. 2018, OECD-MA Art. 13, marginal note 77a. Reference also to Section 1 (5) AStG and Section 6 Betriebsstättengewinnaufteilungsverordnung – BsGAV and Haun/Klumpp, Allocation of holdings to the business assets of a partnership, IStR 2018, 661.

16For the current legal status of the infection, see Korn/Scheel, DStR 2019, 1665.

17See BFH ruling of April 28, 2010, I R 81/09, BStBl. II 2014, 754; Pohl/Raupach, DBA, § 50i EStG and commercially oriented partnerships, in Wassermeyer, Double Taxation Agreements, Festgabe, p. 351; Schaumburg, International Tax Law, 4th edition, 295-298. Reference to § 50i EStG.

18In a non-DBA case in the so-called “Chile ruling”, the BFH demanded a causation test for this view; ruling of November 29, 2017, I R 58/15, IStR 2018; 348. Wacker, DStR 2019, 836.

19See BMF letter of September 26, 2014, BStBl. I 2014, 1258, marginal note. 2.3.3. for DBA and non-DBA cases. See Hoheisel, IWB 2008, 2010. With regard to a non-DBA case, the BFH has at least in principle affirmed the commercial character, BFH ruling of April 26, 2017, I R 27/15, DStR 2017, 1913 (“Chile ruling”).

20BFH ruling of September 17, 2003, I-R-95/01, I-R-98/01, BFH/NV, BFH/NV 2004, 808; FG Müntser, ruling of December 15, 2014, 13 K 624/11 F, EFG 2015, 704; Ditz/Tcherveniachki, DB, 2015, 2897; Kessler/Arnold, in Kessler/Kröner/Köhler, 3rd edition, 2018, § 8, marginal note 224; Haun/Klumpp, IStR 2018, 661.

21See Strahl in Kösdi 2007, p. 15657, marginal note 20; BFH ruling of August 7, 2004, VIII R 28/02, BStBl. II 2005, 48; H 17 Section 4 EStR 2019 “retransfer”.

22See Stümper, GStB 2015, 171; H 17 Section 4 EStR 2019 “reserved usufruct”.

23See Bron, IStR 2016, 26.

24See OFD Frankfurt of December 3, 2015, S 2134 A-14-St213, marginal note. 29.

25Regarding the state of opinion on which shares are covered by Section 6 AStG, see Müller-Gosoge in Haase, AStG/DBA, § 6 AStG, marginal note 51. See also BFH ruling of December 19, 2007, VIII R 14/06, BStBl. II 2008, 659 on expectancies within the meaning of Section 17 EStG; H 17 Section 4 EStR “option right”. See also BFH ruling of July 11, 2006, VIII R 32/04, BStBl. II 2007, 296 on the double option, through which beneficial ownership can already pass to the option holder before exercise. In H 17 Section 4 EStR “Beneficial Ownership”, the tax authorities write somewhat contradictorily to the above ruling with regard to the BFH ruling VIII R 14/06 that beneficial ownership in the case of acquisition options can only be established if, according to the typical course of events decisive for the economic assessment, an exercise of the option right can actually be expected. In this respect, the taxation of expectancies under Section 17 EStG differs from the taxation of non-tradable stock options that are granted to an employee at a reduced price. Non-tradable stock options are only subject to German wage tax when the option is exercised.

26Judgment of the Schleswig-Holstein Tax Court of March 31, 2020, 4 K 113/17, nrkr. Revision pending under I R 52/19.